The Triumph Bonneville was perhaps ‘the’ motorcycling sportster of the 1960s – so what does that make the rare ‘Thruxton’ production racing variant?

Words: IAN KERR Photographs: TERRY JOSLIN

There could be a good case argued that the Triumph Thruxton Bonneville was one of the most stylish in the Bonnie range of original Meriden Triumphs, while it definitely remains one of the most desirable and sought after, with prices staying high despite the current softening prices of other classics.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

If you don’t believe me, Bonhams’ auction sold one of the original batch of Thruxtons at their early Stafford auction in 2024 for a sum well in excess of £15,000, which is not too far below the early-£20k they were selling for a couple of years ago, and still far above what a ‘standard’ matching numbers Bonneville would fetch these days.

I have used the term ‘original,’ because when you start looking at the model’s history, things start to get a little interesting as to exactly what constitutes a Thruxton. As most will know or deduce, the Thruxton was named after the race circuit in Andover, Hampshire, which ran an annual race for production motorcycles, over 500 miles around the 2.4mile circuit, created around the old airfield perimeter track. The race, not unsurprisingly, was called the Thruxton 500.

The first running was in 1955 and it was originally called the ‘Thruxton Nine Hour Marathon’, and it took place on the longest day of the year. The first three editions were all won by BSA machines. Soon, mileage instead of time became the crucial factor and the name was changed. Nonetheless, it was still seen as a very prestigious event and all of the major manufacturers took time to enter two-man teams.

Just for the record, there were 12 Thruxton 500 events run between 1958 and 1973, although there were four races (1965-68) where it was run at Castle Combe and then Brands Hatch because of poor track conditions at Thruxton. Certainly, the race was very important to British motorcycle manufacturers as a top three place offered excellent advertising opportunities and boosted sales.

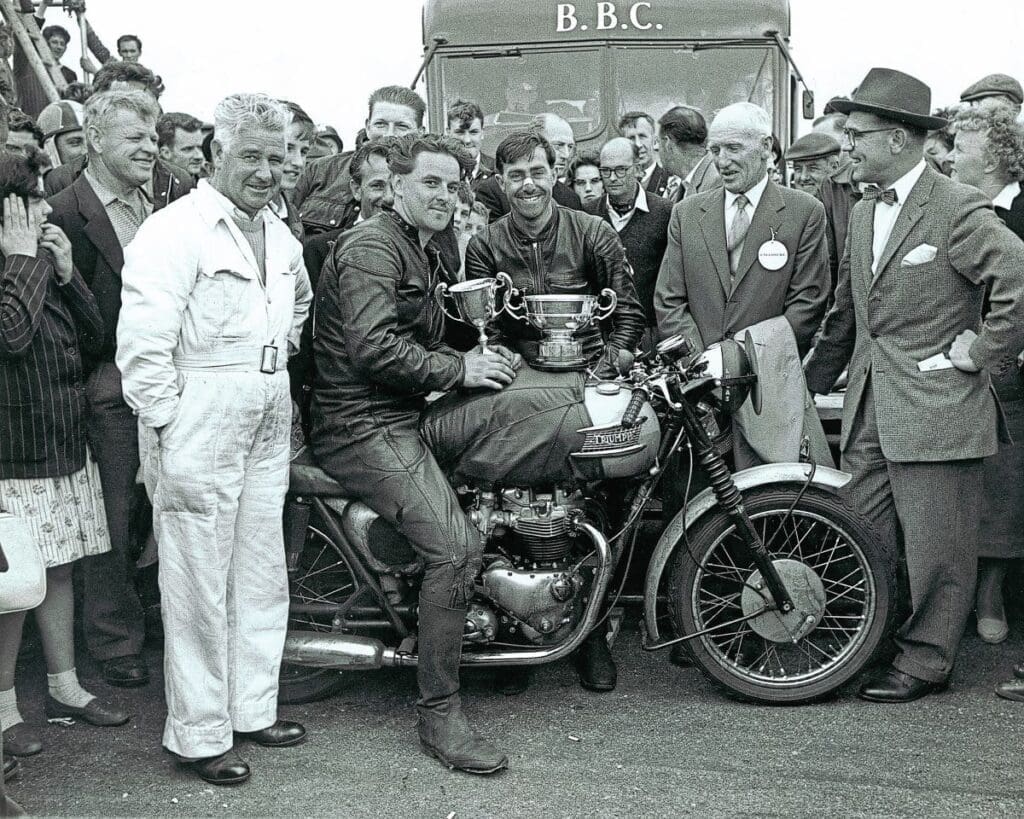

In 1958, Triumph managed a win with a two-lap advantage on a 650cc T110 ridden by Mike Hailwood and Dan Shorey. John Holder and Tony Godfrey won again for Triumph in 1961 on a T120R Bonneville and it was then the Thruxton name came about.

Well respected author Dave Minton, in his book ‘The Triumph Story’, cites an advert by the factory in The Motor Cycle as a result of this win, as reading; ‘Thruxton Triumph by Bonneville’ starting the first public association of the two names.

But, for the next three years Norton were the main winners, thanks to Doug Hele, who ironically had moved to Meriden in October 1962. Hele was responsible for the road-based 500cc Domiracer (third in the 1961 Senior TT) and his 650SS went onto garner those three consecutive wins. He was of course charged with making the Bonneville a winner in the same vein, thus starting the Thruxton development story, among other projects.

Moving on, most authors say that the first and only bikes to bear the Thruxton moniker were built in 1965, in a batch of 50 to comply with production racing rules and regulations, although due to the theft of a cylinder head (still an unsolved crime) only 49 were actually completed. But, in his seminal work ‘Triumph Thruxton Bonneville 1959-1969’, author Claudio Sintich quite correctly points out that the first two bikes were actually built in November 1964.

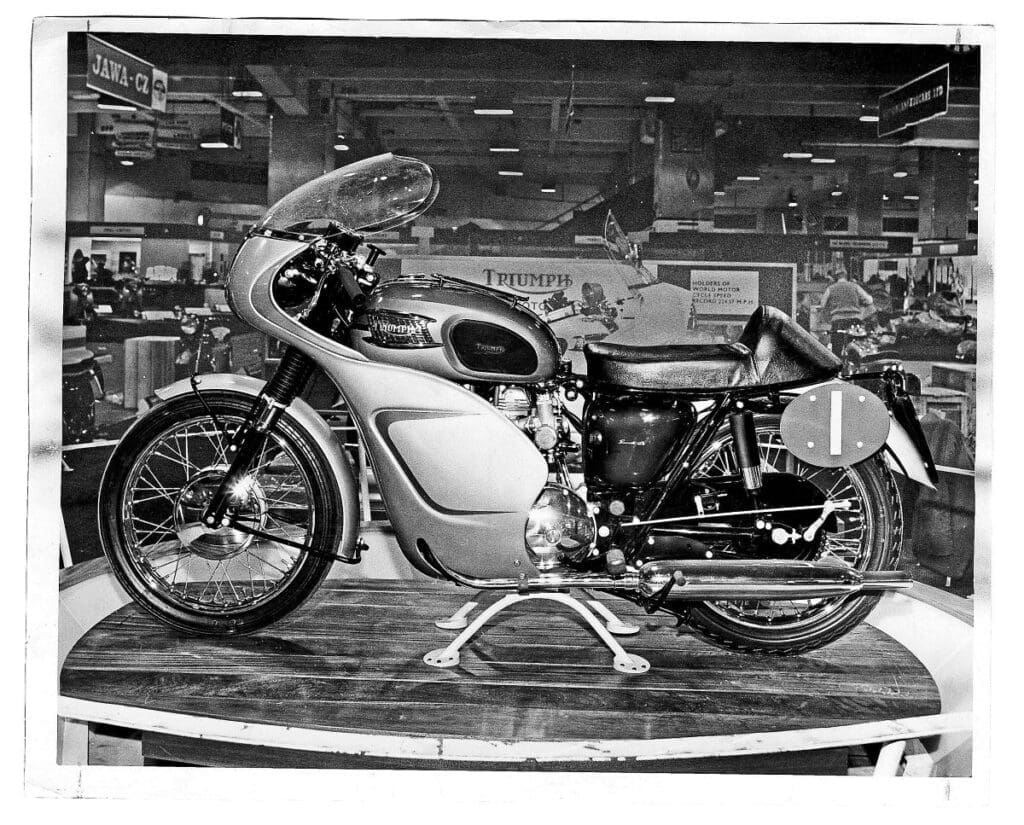

Authenticating this, he quotes from Harry Woolridge, who explains that he and Arthur Jakeman, both from the experimental department, built the 1964 show bike, frame number DU15352. Despite the fact that the bike that was on show to the 130,000 visitors who flocked to Earls Court it had not been priced, but it was apparently sold! In 1965, the price was announced – £357-9s-3d.

Wooldridge states that 52 bikes were built on the normal production line, but were finished off by a small team at the end of the line fitting special parts, plus the four show bikes completed the year before, making a total of 56. Apparently, the company did not bother to produce a brochure, for reasons we will come to, but did list the ‘Alternative Extras’ to turn a standard Bonneville into a Thruxton as well as ‘Maintenance Data’ for the performance machine.

It should be noted that ironically in the same year the bike was created, the 500 mile race moved to the Castle Combe racetrack in Wiltshire. But Triumph did get the win with Dave Degens and Barry Lawton in the saddle, thanks to the preparation work done by tuning expert Syd Lawton.

It is doubtful that the Avonaire fairing made by Mitchenall Bros as an option designed to increase top speed had any real benefit on the much tighter track.

The bikes were in every respect ‘blueprinted’ and assembled from the best components available and were light years away from something an enthusiast could buy. Each was sent to dealers with racing experience and although the parts were listed as above, Triumph were very much in control of who got what.

Speaking recently to George Hopwood, he confirmed that there was lot of support given unofficially to dealers then and later on, with engines and components arriving without any invoices or paperwork, so those in the company opposed to racing were none-the-wiser as to the help being given to keep the Triumph name on the top podium step.

Apparently, there was no intention of repeating the production run at the factory as these bikes were produced solely to meet the race regulations, and there was no plan to create a customer model for general sale.

Without getting into all the modifications, touring camshafts E4220 were used with larger three-inch radius cam followers. To combat increased wear as a result, they introduced positive lubrication to the exhaust cam, which would find its way onto the standard bikes a year later. Carburettors reverted to chopped 1 3/8 Amal Monoblocs with a central remote float chamber.

The now distinctive free-flowing cigar-shaped exhausts held in place by flat metal straps helped up the power to 54bhp, over a standard bike’s 47bhp. Although that figure was quoted on a standard gearbox, rumours suggest a few were fitted with close ratio boxes.

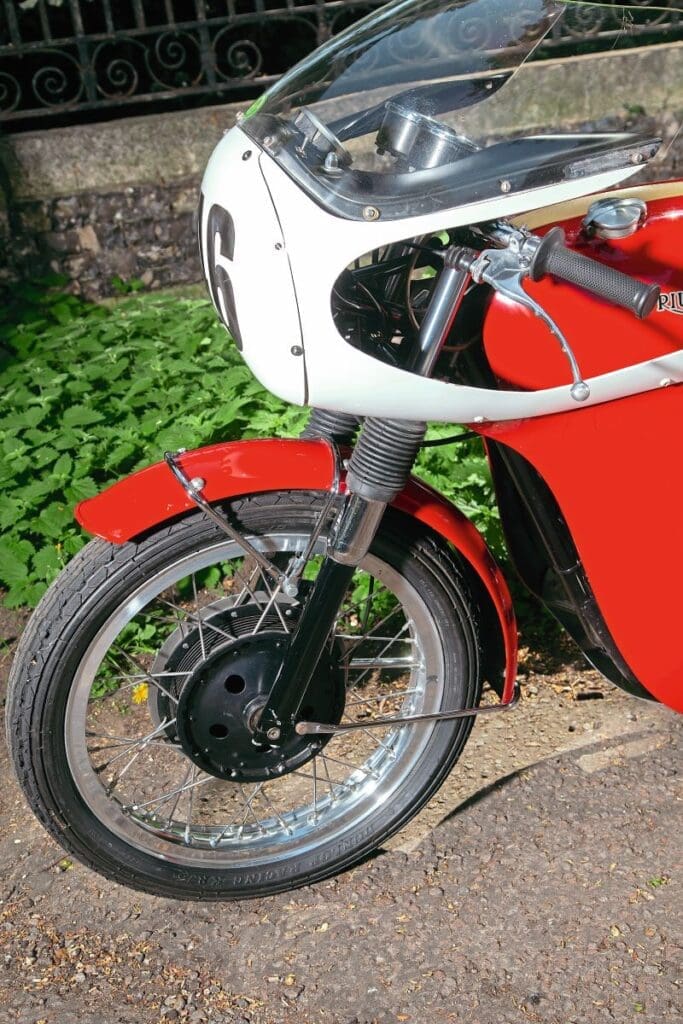

The frame’s steering head angle was steepened (62 instead of 65 degrees) moving the weight distribution further back, the forks had shuttle valve damping, which again would find its way onto later standard models. Other changes included 19-inch wheels front and rear and a ventilated eight-inch front brake.

To meet regulations, the handlebars had to be clamped to a standard top yoke, but ‘Thruxton Bend’ bars were used to get something of a racing crouch more suitable for competition, along with a single seat with a rest at the rear.

Most of the bikes were produced in the Triumph blue and silver colours and a few more Production racing T120s were prepared for dealers, and the Sintich book ably chronicles many of these other machines still referred to as ‘Thruxtons’.

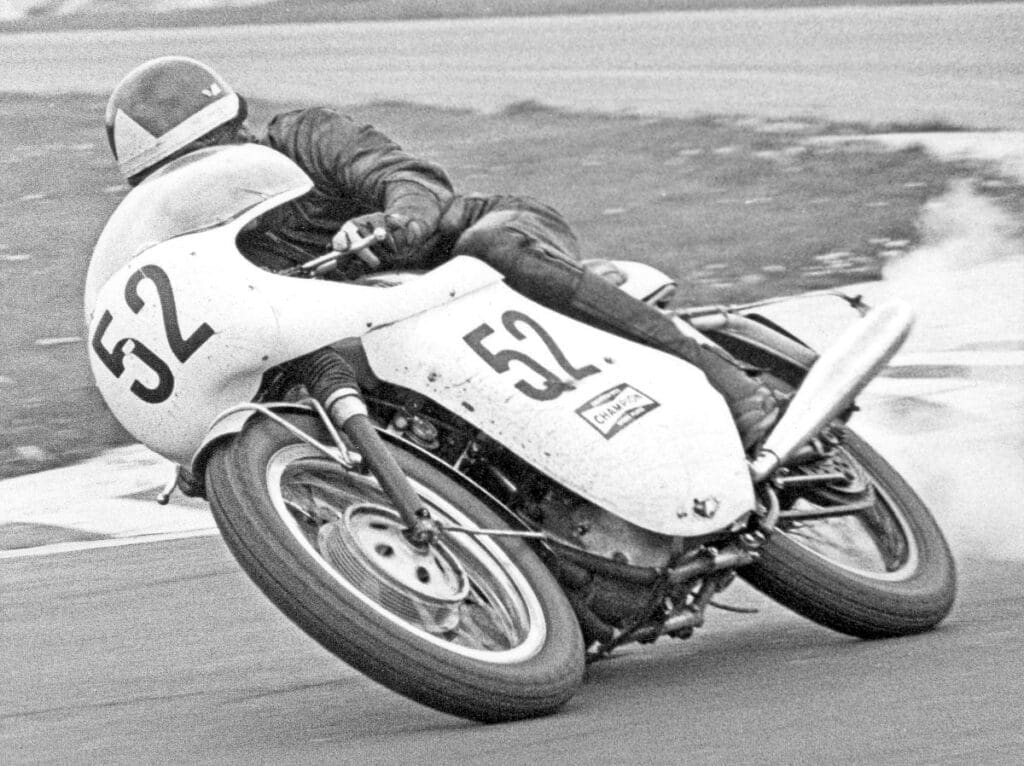

Ironically, it was in the last year of use when the bike really hit the headlines of the world’s press, thanks to a Welsh rider by the name of Malcolm Uphill. Timed at 134.5mph through the Highlander speed trap in the Production TT, riding MAC 232E, Uphill became the first to lap at over 100mph (100.39mph) on a production bike over the full TT circuit, with a record making 99.99mph race average.

The factory’s interest soon turned to racing the triples and apart from helping a few dealers with Thruxtons for the next three years, gaining some notable wins, the Thruxton had had its day. So bearing in mind the aforementioned, what exactly is a Thruxton? Is it one of the ‘original’ 50/56 or does one of the bikes modified and raced later really qualify for the moniker?

The owner of this superb example Pat Meehan is in no doubt that this is a genuine works bike and has the documentation from Meriden to back it up. In a letter from Darryl Pendlebury – who also raced Triumph twins with great success – on headed paper dated September 1974, he confirms that this bike originated from the Experimental Department in 1968 and was used in the Thruxton 500 at Brands Hatch, ridden by Percy Tait.

It goes on to state although most bikes were blue and white, red was also used. In terms of the chassis, he suggests the bike should have parallel yokes and shortened stanchions, and fairings and seats came from Bill Jakeman.

According to Pendlebury, a works engine, which this has, produced 64.6bhp with a compression ratio of 10.4 to 1. He conforms the larger followers and the different camshafts. Ignition was apparently standard and some bikes had Quaife gearbox internals.

Though he also was in 1969…

It should be noted that Darryl has subsequently seen the bike at a TR3OC track day in the last couple of years and in fact awarded a prize for the best Thruxton, noting its originality, as did Paul Smart when he saw it on display at the now defunct London Motorcycle Museum. Paul recalled he rode the bike after Tait and finished third in his first outing in the Hutchinson 100 Trophy at his local Brands Hatch circuit, before following it up with a win at Crystal Palace, and many more afterwards.

So the story as to how Pat came to own an ex-works bike is in itself fascinating and a matter really of chance and coincidence. Arriving in London from a relatively poor area of Ireland in the early 1960s, young Meehan had rarely seen a motorcycle.

Living close to the Reg Allen dealership, which he, like many others, thought was run by a man of the same name, he came across the proprietor, one Bill Crosby, whose story has been told in this magazine some years ago. Needing transport, Pat bought a brand-new BSA C15 from him, which later got traded in for a Triumph sprung hub machine that had a Steib chair attached.

A series of unreliable mounts followed, before a totally reliable LE Velocette was found, causing Pat to end up helping Crosby maintain not only his bikes, but he got involved in helping with the sponsored machinery.

Crosby was well known for supporting motorcycle sport; for instance, backing Nick Thompson who competed in the ITV World of Sport Scrambles Championship and Pat remembers Bill was ‘one hell of an engine builder’.

However, it was road racing that hooked Pat in, when he was asked to passenger Peter Tyack in the Isle of Man, who was another Crosby sponsored rider. ‘No experience necessary’ was what he was told and he remembers fondly his time at the TT, eventually getting his own outfit and mixing it with some of the sidecar greats on short circuits in his racing years.

However, it was pure chance that while out on his LE Velo, he was passed by a bright red Triumph Thruxton going in the opposite direction and he thought ‘I must have one of those,’ regarding it as a dream bike. Several days later, while riding past Reg Allen’s, he saw the bike outside. Enquiries showed that Bill had bought the bike as part of a trade and eventually a new deal was done which involved Pat parting with £375 – a considerable sum when his wages were just £30 per week.

Ironically, it did not come with any history as to how it had become ‘just another road-going Triumph’ and all the previously mentioned information has been obtained subsequently.

After regularly using it as a means of transport despite still being involved in racing, eventually the bike was taken off the road and restored. It was fitted with electronic ignition and a few other sensible mods without destroying its provenance, and it then graced the London museum until its closure a couple of years ago, in between being taken out for various classic track days.

Sitting gleaming in the sun for the photo session, it certainly looked stylish and purposeful and attracted a lot of attention from walkers, many of whom were elderly women who said it reminded them of carefree days riding on boyfriends’ bikes, the wind in their hair. Funny how the older machines always attract a favourable response, much more than modern bikes.

Inside the fairing, a racing rev counter sits below the screen, although the standard road-going one is still in place. Pat said that the additional ones were fitted because the standard ones spent too much time dancing around and were not that accurate for racing purposes.

When it came to the action shots, Pat showed that providing both carbs were flooded, it was first-kick starter, quickly settling down to a pleasant and unthreatening exhaust note even when the throttle was blipped. However, when Pat opened up on the fast, sweeping bend we found for photos, it sent shivers down your spine, reminding you of its glorious racing past and he was clearly enjoying the chance to open the taps. Obviously, it would have been nice to have the use of a proper race circuit to really push the bike, and no doubt it will get a few outings again this year, but nonetheless it was a pleasure to see what the factory did achieve when they put their minds to it, unhindered by politics at the top of the tree. Certainly, there is no doubt that Pat’s bike is a true Thruxton Bonneville in every respect, with the provenance to back up its claim to fame.