What should you do if you find yourself with a load of old Indian motorcycle bits? Why, build up a machine, obviously, as best as you can and with what’s to hand.

Words: IAN KERR

Photographs: TERRY JOSLIN

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Wisdom says that there are two sides to every argument, the pro-side and con-side, in other words two-sided arguments present both sides of an issue. In respect of written arguments, it should present a balanced and objective analysis of both sides, because in reality there is a third side – a compromise.

At the risk of starting a massive flow of correspondence, the $64,000 question in respect of veteran, vintage, classic or just collectable motorcycles, is whether to restore, and included in that is originality, and just how far do you go in bringing a bike back to life?

Plenty of people will quite correctly point out that things are only original once, and you should consider whether by doing a restoration you destroy the history of the bike. Returning a motorcycle to, in some cases, better than showroom condition, may make it look good in a museum or somebody’s living room, but is it a true representation of the original model?

Take a championship-winning competition machine. Restoration may remove scrutineers’ labels, paint marks and so on, so do you sympathetically restore to running condition, but leave such things in place? Do you improve certain areas of its mechanism to make it run better, or make sure it is safe to run as the maker intended?

Surely, what cannot be seen inside an engine or hidden is acceptable to some, but not to the true connoisseur?

What about the bikes that are discovered still in boxes. Do you remove them and maybe lose value, and what score do you put on push miles? Do you use as a new bike? So many questions, and all potential answers are valid.

Another consideration has to be that if you remanufacture parts like George Beale did with his magnificent Honda RC166 six-cylinder re-creations, how far do you go, because currently with 3D printing improving daily, you could soon remanufacture a complete bike, and use an old logbook to gain a frame and engine number.

Already there are numerous replicas in the sporting world, both on the track and others off-road. As one ‘manufacturer’ of a very trick lightweight trials bike once told me, all he has done is evolved the machine as the original manufacturer would have, had they still been in business, and had access to such things like carbon fibre, electronics etc. It’s a point well made.

Having stoked the fire, I will now ask the question what happens when you have boxes of bits that can go together to construct a running machine, but one mixing various years of components, and having done that made it rideable and useable? The alternative is of course to sell the bits to those seeking to complete their own restorations.

To truly balance all of those questions and put forward the various arguments for and against would fill the entire magazine, so I will just stick with the Indian featured here, because one man has answered many of these questions from his own perspective.

Graham Tindell has appeared in these pages before with his somewhat fearsome Indian grasstrack racing machine, on which he had considerable success in VMCC events. The grasstracker was built by Graham’s late father Alf, who, as Graham explained, obtained a whole lot of dismantled Indian machines in the early 1970s, and after restoring an original veteran from them which he used in the Pioneer run for many years, he had a lot of leftover parts. Some of them found their way into the grasstrack machine and some of the others you see here on a bike which Graham himself built, when he inherited the parts.

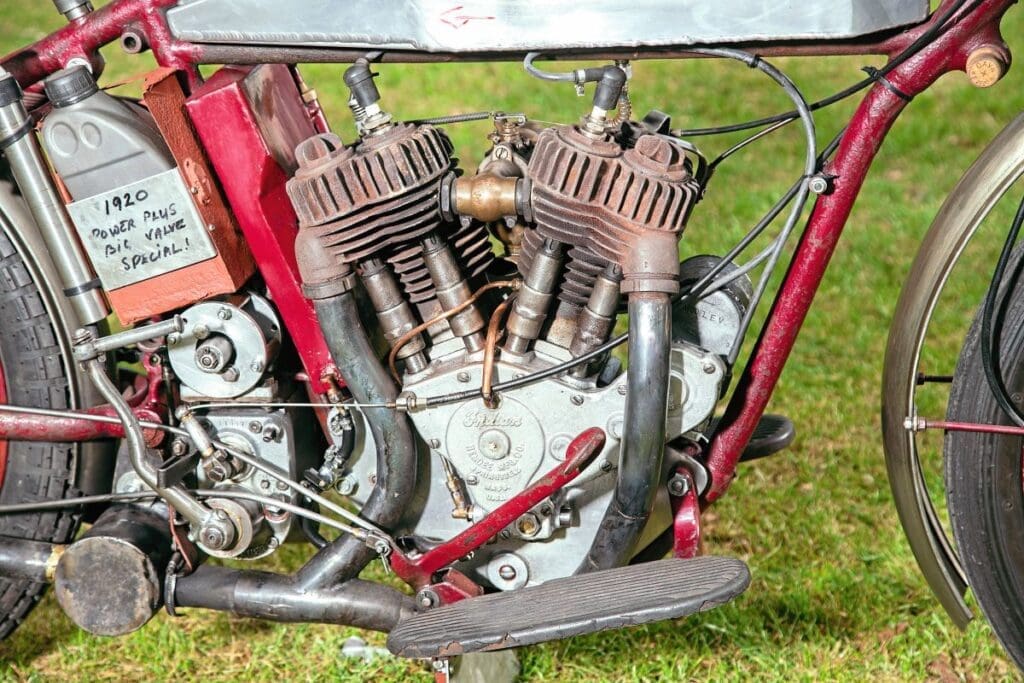

If you were French, you may well call the bike a ‘metisse’ as it is very much a mongrel, but one that is mainly a collection of Indian parts. So to start at the beginning, the bike is billed as, and registered as, a 1920 Indian Powerplus, because that is what the frame and rolling gear is.

Indian had been founded in 1901 when a Swedish immigrant called Carl Oscar Hedstrom joined forces with bicycle manufacturer George Hendee in Springfield, Massachusetts, and had become, along with Harley-Davidson, the main player in the USA, as well as in other countries, thanks to their sporting success.

Indian’s almost complete dominance was due to the fact that Hedstrom was a brilliant engine designer and it was the inlet over exhaust V-twin motor that was exceptional. Resigning in 1912, his place was later taken two years later by Irishman Charles B Franklin, one of the victorious Indian team in the 1911 TT races, when the marque took all the podium positions.

Ironically, when the Powerplus was introduced into the line-up it was powered by a motor designed by one Charles Gustafson, who had moved from another early American company, Reading Standard, in 1909. Although the side-valve motor had really caught on in Europe, it was only the above company who were using them, thanks to Gustafson, who then took his knowledge to Indian and produced the new motor in collaboration with Franklin. This new engine was more powerful than the inlet-over-exhaust design Indian had been using – and it also allowed Indian to stop paying Hedstrom royalties on his design.

The Indian’s frame was a classic cradle design with a single downtube and at the rear it still had the leaf-sprung swinging-arm frame introduced into the 1913 range by Hedstrom before he left, although a rigid version was also available. Some sources attribute the design, though, to one seen before on a Flying Merkel in 1909.

The pivoting fork does so off the main frame, but instead of two shock absorbers either side, the vertical movement is controlled by a pair of laminated springs attached to the main frame and then to the wheel spindle end, by two vertical rods. As you would imagine there is no damping control, but compared to a rigid frame, the three inches of travel at least give some rider comfort.

At the front end, girder forks with trailing links were the order of the day, again with springing being supplied by laminated springs; nothing new there as this was a common set-up for many manufacturers at that time.

The wheelbase was just 59 inches, with both spoked wheels being 28 inches fitted with 3.00inch tyres. At the time of production, there was no front brake and the rear had a conventional internal expanding drum brake with an external contracting band brake working on the drum’s exterior. Neither were any good, so Graham has added a front drum brake taken from a Honda 90 which surprisingly does not look out of place.

The twin top tubes of the frame were now hidden by two, new, more rounded tanks made from pressings and joined by a central strip, as opposed to earlier versions which were hand-built from several sections. The new items were cheaper on a bike still costing circa $390 if it had the electric lighting set (acetylene lights were also still offered) which was an optional order.

Period Indian advertising shots show a Commercial version as a solo and as a sidecar outfit with just a single cylinder 560cc motor in the frame, devoid of lights but otherwise looking identical, but costing just $325 each.

Overall weight at the time was quoted as 430lb with a 60mph top speed. The handling was acceptable, although it was reported to get a bit squirrelly at higher speeds thanks to the suspension moving about sideways.

When the model was introduced in 1916, it was very much the subject of conversation because of the new side-valve engine, not because of the chassis or running gear.

Originally it would have had a 60.88 cubic inch side-valve twin pumping out 18bhp, but maintaining the 42-degree V-twin angle to enable Indian to keep using the same magnetos and other parts. The Powerplus used a slightly smaller bore coupled with a longer stroke than the earlier F-head motor, but used the same single two-lobed camshaft to operate all four valves, and carburation was though a single Schebler unit. Apparently, the main motivation for the new motor and machine was it was cheaper to make, but it sold mainly on the increase in power, rather than price.

Primary drive was via a dry multi-plate clutch and the kick-start was on the left with final drive by chain via a three-speed gearbox. The gear lever was on the right side of the tank, along with a valve lifter and one which also operated the clutch, but was also linked to a left foot clutch lever as well. The right twist-grip operated the ignition advance and retard and the actual throttle was a twist-grip on the left handlebar. It all sounds complicated, but was actually very much a standard set-up for the time.

For Graham, though he did not have enough parts to return the bike to standard, but what he did have was a much earlier ‘big port’ motor, which slotted straight into the frame with no modification needed.

A Sturmey-Archer three-speed gearbox stands in for an Indian version and apparently this is actually a recognised, common modification, and retains a right foot kick-start facility.

As far as the controls are concerned, this is an area where a lot of the modifications have been made by Graham, to make the bike easier to ride and saved hunting for all the original levers and parts. The twist-grip has been moved from the left ’bar to the right ’bar as on most bikes, and a clutch lever now sits on the left ’bar, along with the ignition control for the Splitdorf magneto and the decompressor for the rear cylinder as opposed to valve lifter. The home-made gear change lever on the left can be operated by hand or foot, depending on your dexterity.

A sprung Wassell trials saddle provides rider comfort, while an aluminium petrol tank made by Stuart Digby Developments takes care of fuelling, sitting between the top two frame tubes as per the original early Indian machines. Overall, it retains the essence of the Indian brand and although it might not look the prettiest bike, it certainly goes well and is still very much a 1920s Indian.

Graham uses a small syringe to prime the carb from cold to save lots of kicking and it starts second kick, giving out that glorious V-twin sound from the single open pipe on the right from the two-into-one system, as opposed to a silenced version exiting on the left as per the catalogue specification.

Graham having warmed things up over several runs to ensure all was well, it was then my turn. I must say, having all the main controls on the ’bars made getting to grips with the bike a lot easier than trying to remember which twist-grip did what, along with dancing on various foot controls and moving levers.

The big port motor may well have been over 100 years old, but the power was still there and you can’t help wondering why we now need 200bhp plus on our congested roads, the 18bhp (?) of this machine was certainly exciting enough on UK country lanes for me.

Handling was ‘okay’ but as earlier testers commented, it could be a little vague, but as the frame apparently once had a sidecar attached, it may not be totally straight…

Just for the record, the Powerplus was renamed the ‘Standard’ in 1922 – despite getting a slightly larger engine in 1921 – when the more powerful Chief made its debut, finally to be dropped in 1923, as was the rear suspension system, that would not reappear until 1940 when the Chief and the Four would get a plunger suspension system at the rear.

So to return to those opening paragraphs, having ridden his bike, I find that I am in agreement with Graham’s philosophy of getting a machine out on the road and in regular use, as opposed to sitting in a museum, or someone’s workshop waiting for those elusive parts to appear.

With regard to originality, that extra Honda brake at least gives you some comfort that you may at least stop, more so than my own Triumph from the same period ever did…

As I said at the beginning, actually, there are three sides to every argument – the third being a very nice compromise, as this old Indian proves.