Steve Cooper enjoys twin takes on Suzuki’s middleweight triple, the GT550 two-stroke – and one with a dash of superstar Barry Sheene.

Words: Steve Cooper Pics: Gary Chapman

Where does Suzuki’s middle weight triple sit in your mind? The poor man’s version of a Kawasaki H1 perhaps, or a pale pastiche of the bigger GT750?

Today it’s a bike that’s sometimes off the radar, seemingly because it apparently falls between two stools. Fans of 1970s Japanese classics often overlook the GT550 simply because it’s not the fastest, slickest or brashest of the bunch. And yet once you know the background to the bike everything falls into place rather nicely.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

The Hamamatsu firm were committed to building what they perceived as two-stroke equivalents of Honda’s range of fours. Therefore, the GT550 was supposed to take on the CB500, with the GT750 Kettle potentially out-psyching the previously all-conquering CB750. The clue was always in the GT moniker – Grand Touring. Suzuki had never set out to make blisteringly-fast missiles like the Kawasakis. And yet the fact remains that all of the machines from that time had notable fundamental issues in the guise of handling and braking… they were only ever adequate at best.

Which all brings us rather nicely to this month’s Classic Ride where we sample an authentic original GT550 alongside a slightly more modern take on the subject.

The model had changed little since its inception in 1972 other than the fitment of a disc front brake in place of the previous drum. Buyers still got an electric-start and the iconic three-into-four exhaust system that differentiated the Suzukis from the Kawasakis.

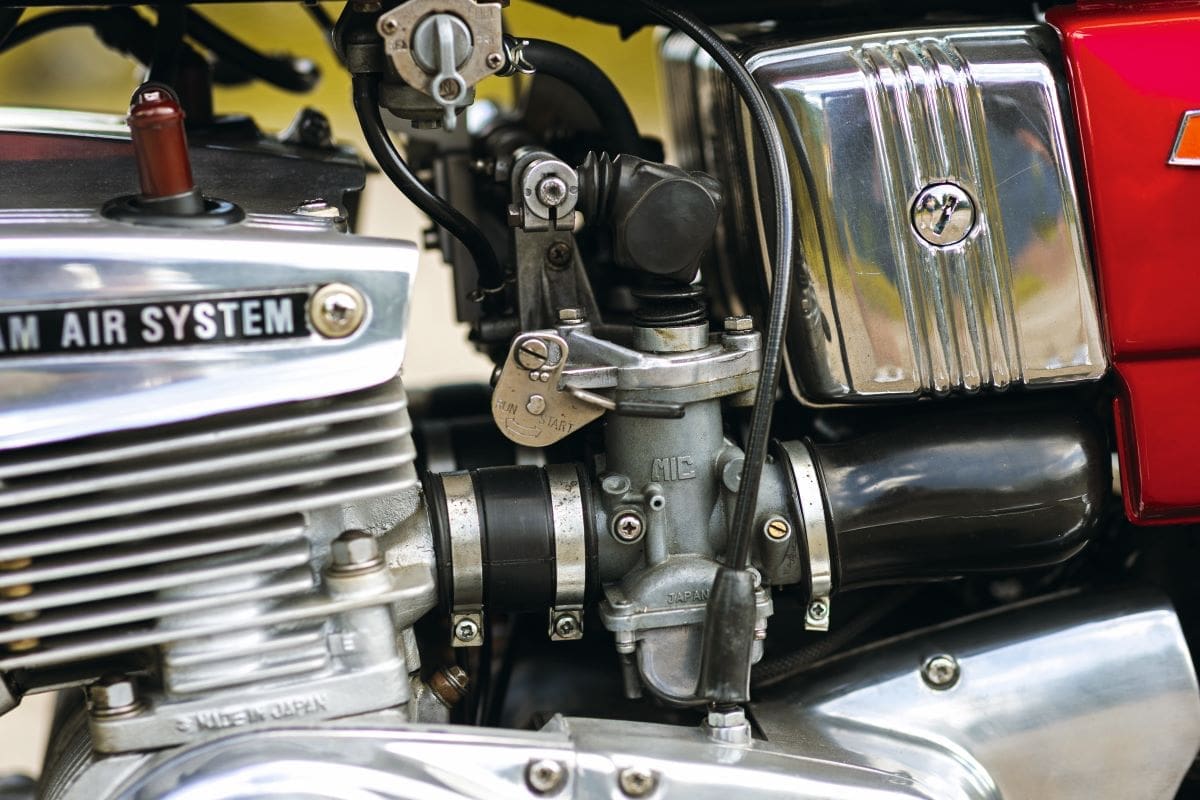

For four years the model hardly changed other than paint schemes and a few trim changes, allowing Suzuki to research other models. Phil Green’s bog-stock 1976 GT550A is the penultimate version of the triple and pretty much as good as the genre got. The compression ratio had been raised to give the bike a bit more pep and the previous iron cylinder liners had been replaced with a ‘SCEM’ coating – a by-product of the ill-fated RE5 project.

Elsewhere, the header pipes were no longer linked via the notoriously leak-prone coupler system; Suzuki chose to sacrifice a little torque for more power. Finally, Suzuki had dropped the notoriously bad plastic gauge lenses and used glass like everyone else, allowing owners to actually see speed and revs instead of peering through cloudy plastic. Sitting here under a blistering sun there’s swathes of resplendent chrome exquisitely counterpointed by Suzuki’s Rose Red paintwork.

Glam rock’s heyday might just have been waning at the time, but looking at the bike in camera you’d be hard pushed to countenance punk rock was just around the corner; the bike is very much a child of the 70s. And yet, with a change in music also came the end of the GT550 with the 1977 B model; two-strokes, flares, and platform boots were old hat – out with the old and in with the new.

The incoming middleweight air-cooled fours might latterly have been termed UJMs (Universal Japanese Motorcycles) but the likes of the CB500/550 and the GT550 here were fulfilling the very same role for a decade or so before.

And in complete contrast is what uncharitably might be described as a ‘bitsa’ by those who get snooty about anything that’s not ‘show grade’ standard or better. Look a little deeper and it is readily apparent Nick Davey’s 550 is a masterclass in what our colonial cousins refer to as a resto-mod.

Truth be told, the bike is more of a 1970s stocker with modern classic upgrades from disparate sources. If you care to study the pictures you might just notice… late model XJR1300 swingarm and forks; early model XJR1300 yokes/ wheels; Yamaha Sumitomo/Blue Spot calipers; Brembo Racing radial adjustable-ratio front master cylinder; reverse-action, pull-type rear with a home-made linkage to the original lever; home-fabricated seat based on a Harley XR75 flat-tracker unit; and Kawasaki ZX-6R switch gear. And those are just the obvious bits. There are various ways of adding these and similar to a project like this but, arguably, it takes a touch of genius to ensure the end result not only functions properly, but also doesn’t look like a dog’s breakfast.

From an aesthetic perspective there’s sufficient GT550 still there in the form of the tank, side-panels, air-box, headlight, and instrument binnacle to readily identify the bike.

And by way of subliminal confirmation the period Forward Trust ‘Sheene’ paint scheme shouts 1970s Heron Suzuki Race Team from the roof-tops. Hopefully, few would decry the use of modern Jim Lomas JL expansion chambers on such a project and they most emphatically do a better job than many of the period aftermarket offerings. Bearing in mind that the bike started as a bare rolling chassis with boxes of ‘odds-n-sods’, only a misanthrope would find issues with the end result. Personally, I rather like the final product. With both machines warmed up via some enthusiastic owner use it’s time to sample them and see how they stack up.

Let’s go ride!

The stock 550 is as neutral and predictable as you’d expect. Two-stroke CB500/4? Yes, pretty much and none the worse for it, but with more character and less urbane civility.

The motor is smooth but not Honda velvety, which means it somehow feels more alive and involving. The subtly under square motor majors on torque propelling the bike with gusto, but don’t expect throttle-induced wheelies. The bike’s key strength is comfort which is totally in line with its Grand Tourer appellation design ethos. The GT550 is the polar opposite of the fiery, H1 be under no illusions here, but then there’s something like a 10bhp difference on power outputs.

And yet it’s just so enjoyable to ride – the looks, the feel, the delicious gurgle from the unique exhausts, the chrome and red paint all combine to make for an involving, fun, ride. Negatives? No, not really, more observations based on how far we’ve come since 1976 to be honest. Anything with a 19-inch front wheel from the period feels slightly slow to turn nowadays and the disc brake is very much ‘of its time’, but you have to accept such nuances if you’re a fan of 70s classics, surely? As a well-rounded package the GT550 still hits the spot perfectly.

And so to the decidedly non-stock version – where do you start? It’s definitely a Suzuki GT550, but not as we know it.

The Renthal bars and lower seat give it a distinctive riding position and the changes to the suspension and wheels alter the static feel as well – it’s not wrong, just different. A quick stab of the starter button has the bike benignly growling through those pipes ready for action. Into gear, clutch out and we’re away on what I can only call a GT550 for the 21st century; the transformation is remarkable.

It’s effortless to ride, instinctive if you will, and there’s not a single, solitary, ounce of ‘cobbled together’ feeling about it. The whole thing works as a cohesive unit, rather suggesting there’s naff all wrong with Suzuki’s original chassis – if there were any deficiencies they’re either at the back of Nick’s garage or in the recycling waste stream now.

The Yamaha suspension and wheels are presumably more than up to the job in hand with capacity to spare, yet they don’t overwhelm the situation either. How good is the bike? I find myself feeling almost instantly at home and enjoying the experience; the seat may be little hard for my lardy derriere but that’s a small price to pay. As you’d hope, the brakes are more than up to the task and work in ways most classic fans can only dream of.

The wide, modern rubber sticks like the proverbial, encouraging you to open the taps early just to hear the three spannies give vent to their feelings. It really is an enthralling experience.

Which is best?

The most obvious question I suppose is which one I’d choose given the option, and that’s a hard call.

You’d have to be a Philistine of epic proportions not to appreciate the thought and craftsmanship that’s gone into the modified GT550, which has not only changed the bike’s profile but also revolutionised the way it handles and stops. On the other hand, the standard GT550 is as good as they get and easily a restorer’s reference point – they really don’t get much better.

Decision time… I’ll have both please. The modified example for some serious road work and the standard A model for a long-distance tour. We can all dream I guess?

Owner’s story – Phil Green’s Suzuki GT550A

This is my third 550, the first I had when I was 21, and my endearing memory of that bike was when I went to the South of France on it with my girlfriend (now wife), all loaded up and it never missed a beat.

I sold that for a GT750, but alas there was no comparison – apologies die-hard Kettle fans – but put simply the 550 is a sports tourer whilst the 750 is a grand tourer and I was more suited to the former.

I just love its lines (the A model is my particular favourite) and oh, the sound of that triple engine through the three-into-four just does it for me!

Performance-wise, it’s not feisty like my 350LC or as lairy as the H1 or H2 Kawasaki’s that I’ve owned but it’s dependable, comfortable and reliable, and for a two-stroke that’s no mean feat. It’s hard to believe it’s been around for over 50 years and I think its styling still stands out today.

Owning one isn’t too bad but standard exhausts are now well past their best and acquiring solid ones is all but impossible. Although there are specialists out there that can open them, weld them, make them good and get them chromed, it’s all for a price, of course. The only downside to restoring early Suzukis is that there is so much chrome, that the bill can be eye-watering.

Electric starters can be problematic. I had to replace the starter clutch on mine. Oh, and I also fitted an Accent Electronic Ignition. Long live GT550s!

Building the upgraded GT550 – Nick Davey

I owned a black GT550A back in the late 1970s. I loved it at the time, although I’ve always had a leaning towards the non-standard, and it went through various incarnations, including a three-into-one expansion system which sounded awesome but killed the mid-range, and a three-into-three Allspeed system, which was lovely. It was never a sports-bike.

After I retired from racing, I had some time on my hands and began to get into restorations and older machinery, and began to think of getting another GT550, but maybe bringing it a bit more into the 21st century regarding handling and braking.

I picked up this machine which was basically a rolling chassis and wheels, with the bottom half of the engine. Everything else was in boxes and bags. I completely rebuilt the engine, including having the bores renikasil plated, a full crank rebuild with new bearings and seals, new pistons, all new gearbox bearings… and so on. I wanted to retain the twin-shock look, so after some research opted for the Yamaha swingarm to carry a 5.5-inch rear wheel. It needed a fair bit of modification to narrow it to fit the GT frame, and sleeving to carry the original GT spindle. I also had the rear shock mounts moved and rewelded for better alignment with the frame mounts. Probably the biggest difficulty was getting the chain run correctly. I had the sprocket carrier machined down about 8mm, to bring the chain closer to the rear tyre, and had a bespoke +12mm offset front sprocket made. I also went to a 520 pitch chain to give a few millimetres additional clearance to play with. The new front end meant the rake remained as standard for the GT, but with less offset for a slightly shorter wheelbase and therefore, with the 17-inch wheel as well, faster steering. The forks are longer than the original GT items, but with a pair of 17-inch wheels rather than 19 and 18 this easily compensates for the loss of ride height. In order to keep the stance right, and keep weight more over the front end, I went for longer than standard rear Hagon shocks. The weight distribution is exactly 50/50 front/rear, but I’d prefer a slightly more forward biased weight distribution. I’m still toying with static sag, spring weight and preload to bring a bit more weight forward. Wet weight is 180kg: about 30kg less than the standard machine. The seat unit is home-fabricated, extended with ally sheet and fibreglass. The rear sub-frame rails have been shortened by about 120mm to bring everything forward, while the tail lights are cheap eBay LED things that I liked the shape of. Marying up the wiring to the GT harness was a project in itself! In the end it turned out fairly close to what I’d originally envisaged, but as with any project like this you have to be prepared to adapt and adjust as you go along, as things won’t fi t, or just don’t look right. There’s quite a lot of trial and error involved.

Mostly I get very positive comments when I’m out and about, but obviously there will be people who don’t like it, or who think I’ve ruined a lovely old bike. I’m fi ne with that as taste is very subjective and it’d be a very boring world if we all liked the same stuff! I think what I like best is the view from behind – the 180 rear tyre with the high seat unit and those exhausts. I’m very happy how that turned out. People sometimes ask me what style it is; I didn’t set out with a particular style in mind, but I suppose there’s a nod to the old flat-trackers, but I don’t know: you tell me? It is what it is.

Specifications

ENGINE TYPE: 543cc, air-cooled, piston-ported, two-stroke, triple

BORE AND STROKE: 61.0mm x 62.0mm

CLAIMED HORSEPOWER: 53bhp @ 7500rpm

MAXIMUM TORQUE: 38.7ft/lb @ 6000rpm

TRANSMISSION TYPE: 5 speed

COMPRESSION RATIO: 6.8:1

CARBURATION: 3 x Mikuni VM28SC

TYRES: 3.25 – 19 (F) 4.00 -18 (R)

FUEL CAPACITY: 3.3 gallons (15 litres)

BRAKES: Single disc (F), drum (R)

DRY WEIGHT: 200kg (441lb)