In that transient time of BSA in the 1980s, the Tracker and Rambler models aimed to bring a younger generation to bikes. Few examples survive…

Words and pictures by Oli Hulme and the BSA Owners’ Club Archive

As the British motorcycle industry disappeared up its own exhaust pipes at the end of the 1970s, there was a small flurry of activity that saw the surviving remains pair up with foreign companies and countries in an attempt to keep something going. The Meriden Triumph co-operative struck a deal with Moto Guzzi to assemble a version of the Italian company’s 125cc two-stroke single on Saturday mornings. The model was badged as a Moto-Meriden Co-Uno and turned out to be a bit of a disaster, as the bike wasn’t very good quality and there were many warranty claims that swallowed up the profits (if anyone has a Co-Uno we can test, please get in touch).

Suzuki very nearly bought a big chunk of Meriden in 1977, but the collapse and revaluation of the Japanese Yen put paid to that.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

The newly-formed Norton Villiers Triumph (NVT) looked at moving production of the BSA B50 single to Iraq and making the Triumph Trident, or versions of it, in the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, Yamaha was working with NVT, providing wheels and instruments for Norton Rotary police bikes, and NVT badged up an XS850 Triple as a Norton to try and capture the police bike market. The link between Yamaha and British factories was helped by the number of former British designers and factory management who had gone to work for Yamaha.

NVT, meanwhile, kept going, with talented designers Bob Trigg (who helped design Norton’s Isolastic system) and Mike Ofield designing a moped which used mostly Italian components with the addition of a few British bits and some Union flag branding. These were sold as the NVT Easy Rider and came in step-thru and sports moped varieties. They were cheaply made and moderately successful, bringing in some seriously needed cash for not a lot of development outlay. The ‘Made In England’ branding still made a difference for sales, and the engine was used in a child’s off-road bike, the Junior.

The Rambler – the trail bike that wasn’t

Something bigger and better was needed, and what Bob Trigg and Mike Ofield came up with was a quite sophisticated project – the NVT Rambler.

What NVT had understood and the Japanese hadn’t was that the British market for trail bikes was very different to the market globally.

The Japanese-built trail bikes were more dirt bike than roadster. They came with real off-road potential, minimal braking and peaky, powerful engines. But the main British market for trail bikes was in young learner riders. They were not buying trail bikes because they wanted to take to the hills… they wanted them to take to the chip shop. If you couldn’t afford a new 250, and few could, and you didn’t want to be condemned to a commuter, a trail bike was stylish option, even if they were not easy to live with on the road.

In 1976, NVT announced that it was going to produce a small learner-legal trail bike. It cut a deal with Yamaha for the supply of oil-injected two-stroke engines from its highly regarded DT125 and DT175 models and started to shop around for the rest of the bits. Wanting to make its new machine stand out, it used a new UK-designed frame with cantilever suspension. Where the frames for the NVT Rambler were made for this new model is lost in the mists of time. One imagines that Norton’s Italian connections regarding making frames for the Commando might have come in handy. Importantly, the Rambler was the very first road/trail bike to arrive with a monoshock, offering the new owner considerable bragging rights. The rest of the bike used some high-quality componentry, too. There was a long shock absorber running under the tank, a set of Marzocchi front forks, reworked Yamaha instruments with NVT branding, Dunlop trials Universal tyres and a very groovy blended-together tank and seat, also sourced in Italy. In fact, about 20 different Italian companies provided parts for the Rambler.

The other big deal with the Rambler was the front brake – something that split opinion. It had a powerful and high-quality Grimeca disc front brake. Those who knew their trail bikes hummed and hawed and spluttered at this. Disc brakes? On a trail bike? That would be far too insensitive for off-road use and get clogged with mud and dust, surely? But NVT understood its market. These bikes weren’t going to go off-road, unless the teenage pilot was taking a detour across some fields after a night in the pub. The disc was far better than the sparse braking on rival machines and much more useful on the road. A Rambler would come to a halt in half the distance of its Japanese rivals.

Recognising that Italian paint quality wasn’t quite as good as it might be, the parts that came in from the continent were finished by the same people who had been painting Commandos and T160 Tridents, and the finish was very good indeed. The side panels were plastic, and the petrol tank held barely a gallon, partly because the monoshock restricted the space available.

The exhaust was designed by NVT, then made by Lafranconi and also finished in the UK. It was given a look similar to that on the old BSA 250 and 500 unit singles. This did cause some issues as Yamaha’s original exhaust curved tightly at the bottom of the barrel, swooping upwards and tucking itself under the seat. Putting the pipe along the bottom of the engine affected two things: the kick-start had to be awkwardly kinked to clear the pipe; and on the 175, Yamaha had big cut-outs on the cylinder head to accommodate the high pipe which were not needed with the low pipe and made the Rambler’s engine look unbalanced. The Yamaha badging was machined off the engine casings and replaced by an NVT sticker.

The headlight was a CEV with a rubber shell and the taillight was the CEV unit used by every Italian manufacturer at the time. Indicators were Yamaha, as was the switchgear. And the front mudguard was tight around the front wheel, an unlikely location for mud plugging. Understanding the market, the Rambler came with a rack, ideal for bungy-ing your school bag to.

NVT made clear in advertising literature who the bike was made for: “NVT took a long hard look at the street/trail market before we embarked on our Rambler project. It is a young man’s market – these single-cylinder dual purpose devices – but the buyers know their machines through and through; all in all, they’re a pretty discerning bunch. Not all of them ride on the rough but they like to know the bike will do it, if required. They demand looks and performance for town riding, plus the specification of a twin-cylinder sports machine for that trip into the country. So, our brief was to provide all the obvious qualities that the British companies do best. Things like a frame that, from the very first weld, is designed to handle with a capital H!

“Lighter too, and more rigid than the opposition. Next came the general geometry. We chose a compact 52.5in wheelbase, dialled in plenty of suspension movement, and arranged everything else to give a riding position that felt right, for everyone – at least, all those in the 5ft 4in to 5ft 10in mould! Oh yes, some of our test riding was done with a slip of a girl on the back, so no worries there…”

Ramblers were made at Shenstone, Canley, and Garretts Green in the English Midlands.

An NVT Rambler cost the same as a Yamaha or Suzuki of similar spec, with the added attraction of that disc front brake and cheaper delivery prices.

The end of NVT and the return of BSA

The Rambler sold moderately well for a few years as it gave NVT dealers something to put in their showrooms. One small South Wales bike shop, Kelsons, bought 25 175s in a single shipment.

In the late 1970s, with NVT in trouble for the last time, a new BSA company was formed, run by Bertie Goodman (once of Velocette) and US BSA aficionado Bill Colquhoon, who bought the BSA name and the NVT designs. In late 1979, the last machines badged as NVT Ramblers were made.

The Rambler got a revamp, becoming the BSA Tracker 125/6 and 175/6.

These trail bikes were the last full-sized BSA machines offered for the road made in the Midlands. Almost identical to the Rambler, the new BSA Tracker’s biggest change was the dropping of the expensive Grimeca front disc in favour of a smaller, more conventional drum brake. The front mudguard was changed to a high motocross type and the indicators went matt black. A short pipe was fitted at the end of the exhaust, blanked off at the end, with two holes directing the exhausts gases and unburnt two-stroke oil down and away from the rear mudguard, which had been plastered with black deposits previously. A handful of Trackers were sent abroad to Ireland, Malta, the Falkland Islands, Malaysia and Argentina.

In 1983, the UK Government put a spanner in the works, banning learners from anything bigger than a 125, which rather damaged the potential for sales of 175cc bikes.

Fortunately, BSA got some help from some rather more welcome government intervention. With international aid funding, the BSA Tracker was provided to Third World countries including to Kenya and Sudan, with the biggest order, for 100 bikes, being shipped to Ethiopia in late 1981 to be supplied to healthcare workers. Elsewhere in this area of the world, BSA’s name still held some weight and deliveries continued abroad, funded by the Crown Agents, a UK government relief agency. BSA moved to Moreton-in-Marsh, in the leafy Cotswolds, in 1986, where a former army base had been converted into an industrial estate. Here the last BSA-Yamaha-engined two-strokes were made, including an off-road-only version of the Tracker which was sold in the UK as the BSA BTX 125-6/175-6. This was basically a Tracker with all the road-legal trimmings removed and a Yamaha exhaust. It was advertised as being suitable for “trail parks and off-road use anywhere.”

What did you get with a Tracker?

The Rambler/Tracker’s motor was the same as the Yamaha version, though the gearing was slightly different, with changes to the sprockets. The Rambler handled better than the original Yamaha 175, though by the time the Tracker arrived, the DT175 had got its own excellent cantilever frame. The Marzocchi front forks were originally used on small Moto Morini models, matching the firmly sprung rear end, this pairing benefitting the handling generally.

It had a rubber 25/25 watt, a pretty feeble 6v CEV headlamp, and the ignition on the 125 was flywheel magneto, while the 175 used CDI. There was a 4amp/hour 6v battery which seems to be there to power the indicators. The Yamaha oil tank was tucked away neatly under the seat. With British motorcycle design long plagued by vibration worries, a lot of effort was put into the use of rubber anti-vibration mounting points. The seat was wide but rather too short for the comfortable transportation of two people and mounting the pillion rests on the bottom run of the swingarm meant that any passenger needed very flexible knee joints, but this was a feature of many trail bikes of the day.

The tank had a range of about 60 miles, so it was not the steed of choice for any cross-country trips. The Tracker’s drum brake didn’t match the Rambler’s disc for power, but was more useful if you did go off-road, and the stiffness of the chassis and the sparseness of the construction made it all work well. As well as improving off-road performance, changing to a drum lightened the front end and consequently the Rambler’s ability to wheelie – vital for a machine aimed at the youth market.

This one is Danny’s

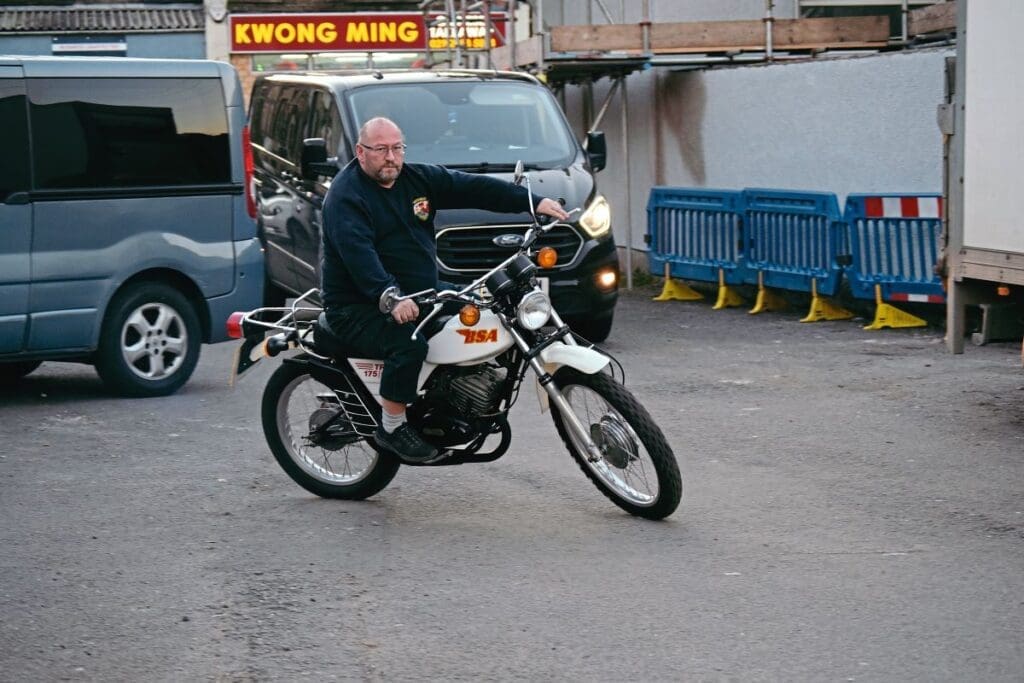

Danny Capaldi first saw this BSA Tracker 175-6 in 2012 in a friend’s collection when providing him with parts for a Kawasaki H1. Danny said: “I’d met Hywel, the owner, on the Moto Piston rally in Spain, and he invited me round. As soon as I saw the BSA, I asked if I could buy it off him, but he said no, he would never sell it.”

When Hywel died, Danny was asked to appraise the collection for sale and was finally able to buy the little BSA. “It was just a dirty version of what you see now. I’ve just de-rusted the tank and sealed it, cleaned it up, and given it a tweak. And I put the ‘Made In England’ sticker on the frame to wind-up all my British bike-owning friends.

“It’s got Italian wheels and forks, and a Yamaha engine and electrics, so it rides lovely. You could start it by pushing the kick-start with your hand. The drum front brake is a bit… meh. It’s not the best. But I’m never going to take it on the dirt. It is a pleasant little runaround.”

With under 8000 miles on the clock, the Tracker’s origins are unclear. Although a late 1979 manufacture bike and one of the first of the Trackers, where it lived during the early part of its life is unknown. The only things that are not stock are the large BSA tank badges and the headlight, which looks more like a custom bike unit than NVT’s original rubber-shelled CEV unit.

Danny, who is listed as the second owner, said: “The DVLA says there are only two 175s on the road in the UK and it’s nice that this one is getting used.”

There is even a possibility that it will be Danny’s bike of choice at this year’s Moto Piston rally.

BSA’s bikes in the 1980s

When the new BSA company took over NVT, the Easy Rider mopeds were rebadged as BSA, but the ER4 sports moped, a four-speed version with a hinged dummy tank, was dropped. Instead, a smaller, lighter version of the Rambler/Tracker frame was pressed into service as the home for a Franco Morini 50cc engine, as used in several Italian sports mopeds. With all sixteener mopeds now limited to 35mph, the appearance of a machine in that class was more important than the performance and the BSA sports 50s were very cute. To cut costs, these bikes were given smaller wheels, cheaper CEV switchgear, more basic instruments and drum brakes front and rear.

The models were known as the Brigand for the trail bike and the Beaver for the roadster, and as well as these there were the unrestricted Boxer and the GT50. The GT50 was also sold in India in some numbers and eventually put together at a plant there owned by the Brooke Bond tea company.

BSA was also assembling Can-Am Bombardier 250cc two-stroke military machines for the British Army to replace their ageing B40 singles. The poky Can Am was something of a revelation for squaddies used to the pedestrian four-stroke singles. BSA used home-produced components as much as possible, including tanks, wheels, tyres, lights and panniers. The Army bought 1000 of these machines and many ended up in civilian hands, though private owners did experience some issues as the workshop manual was unavailable due to it being covered by the Official Secrets Act.

An international aid programme gave BSA another throw of the dice in the mid-1980s, and it was Yamaha which again provided the means. They supplied Yamaha XT125 singles and AG two-stroke farm bikes in kit form, put together with BSA tank badges applied and shipped as the BSA 125/4 for the XT and BSA Bushman for the two-strokes.

BSA was sold again, became BSA Regal, and was relocated to Southampton, where kids’ bikes were made, along with a very classy Yamaha SR500-engined café racer. A prototype 1000cc parallel twin with a Wasp-Rhind-Tutt was produced but sadly never made it out of development hell. And that was it, until…

SPECIFICATION – BSA Tracker 125/175

ENGINE: 123/171cc torque induction two-stroke BORE/STROKE: 56mm/50mm 66/50mm CARBURATION: Single Mikuni COMPRESSION: 7.2/6.8:1 TRANSMISSION: Six-speed gearbox IGNITION: Flywheel magneto/CDI FRONT WHEEL: 2.75 x 21in REAR WHEEL: 3.50 x 18 FRONT SUSPENSION: Marzocchi hydraulic forks REAR SUSPENSION: Single shock cantilever FRONT BRAKE: 160mm drum REAR BRAKE: 140mm drum LENGTH: 84in (2133mm) SEAT HEIGHT: 29.5in (750mm) WHEELBASE: 52.5in (1320mm) DRY WEIGHT: 210lb (94kg) FUEL TANK: 1.2 gallons POWER: 14/16bhp TOP SPEED: 165/70mph

Thanks to the BSA Owners’ Club; Jeff Allen, from the BSAOC Archive, for providing the Rambler/Tracker production records and sales brochures; and Danny Capaldi, of DC Restorations and Vapour Blasting Services, for access to his Tracker.

Owners’ Club

BSA Owners Club

www.bsaownersclub.co.uk

Spares

Parts can be hard to find, but Moped Bug has a stock of some parts for all the NVT/BSA mopeds and trail bikes.

www.mopedbuglimited.co.uk