Words: Rachael Clegg Photographs: Bernard Hargreaves Collection

Bernard Hargreaves’ life has been one of kitchen sink glamour.

Innovator, engineer, Lancashire publican, motorcycle racer and Cold War radar technician, Hargreaves’ experiences scream with colour.

And as if the stories weren’t enough, they’re accompanied by Bernard’s rich, Clitheroe-shaped language.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Hargreaves fell into racing – quite literally – when he was a young boy riding his dad’s Velocette. “I was riding down Hawthorn Lane in Clitheroe on a Velocette with a three-speed Sturmy Archer and it was my first attempt at a foot-change gear and I crashed into a garden fence.

I fell into it and part of the fence speared into my left knee just above the joint. I dashed to my gran’s garage and was then sent to the GP. When I got home I was in a lot of trouble!”

As his punishment, Hargreaves was asked to saw up timber for his father, but instead managed to persuade someone else to do it in exchange for fixing his AJS.

“There was a man who stored his AJS at the shed and he offered to saw the wood if I fixed his bike.” Naturally, Hargreaves relished the opportunity to get his hands on the bike.

Born in 1929, the war ended just as Hargreaves turned 16. Ongoing petrol rations didn’t affect the progress of his motorcycling career as his father ran a modest haulage company, which allowed the young Hargreaves to keep his hobby topped-up.

After refining his two-wheeled topiary, Hargreaves moved onto riding on the roads, much to the relief of Clitheroe’s suburban residents.

His first road bike was a Model 50 Norton, which he used on the roads and also on dirt tracks as a make-shift scrambler. Hargreaves’ road-racing debut was in 1947 at Altcar, near Liverpool, racing a pushrod Norton against the likes of Eric Briggs, Denis Parkinson, Stan Barnett and Fred Wallis.

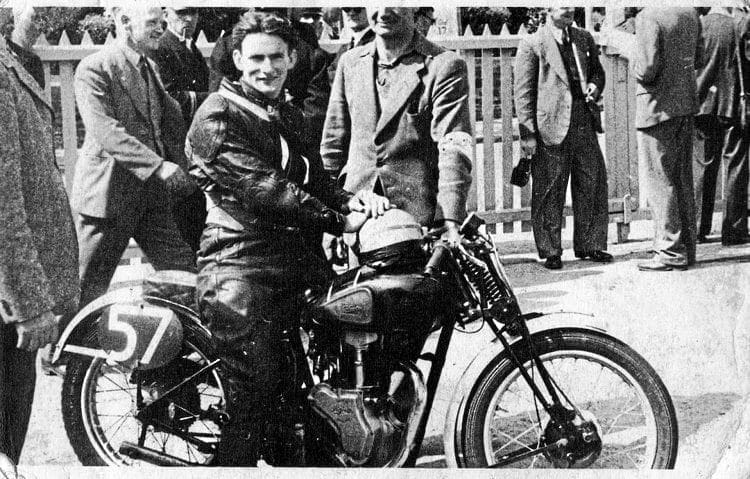

Soon the Norton was replaced with a 250cc Velocette MOV and by 1949 he’d progressed enough to qualify for the Clubman’s TT.

It was a successful debut. Hargreaves came third in the 250cc Lightweight TT, but the following year was less successful after his prop-stand lug caught the road. Hargreaves fell off and broke his leg.

However, two years later came Hargreaves staggering, physics-defying victory, at the 1950 Clubman’s TT.

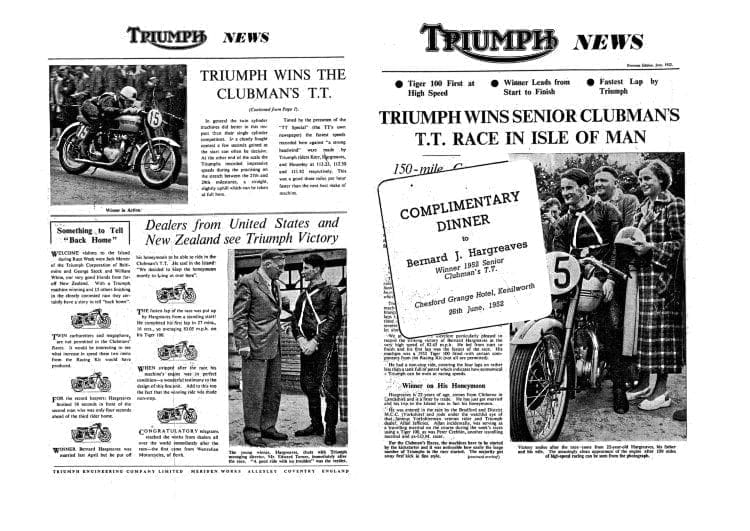

That race – Wednesday June 11, 1952 – saw 87 starters set off in groups of three at 30 second intervals.

Hargreaves was one of 28 Triumphs, but none of them were to experience the drama that Hargreaves was put through in what must have been a most gruelling race.

Hargreaves’ idiosyncratic block capital notes tell the story. “I had the race won, in theory, before it started,” he wrote, in spidery ink.

“I expected a win and a fastest lap.” This was clearly an occasion that verifies the theory of mind over matter. Hargreaves’ triumphant premonition came true: he won the race in spite of his back wheel nut breaking loose.

While this would have been a terrifying prospect for most riders, for Hargreaves it was nothing more than a hiccup that required some creative thinking.

“I had no option but to keep the ‘rear top run’ holding the wheel in situ. And I screwed the steering damper, which must have looked awful negotiating those slow tight corners.”

As if a precarious back wheel wasn’t enough of an obstacle, Hargreaves also decided to gamble on his fuel supply.

“I figured that I could just about do it without a pit stop. I just had to take all areas in as high a gear as possible to build up a fuel surplus.”

It wasn’t just to save time that Hargreaves decided not to make a pit stop. “If I’d have stopped and they’d spotted I didn’t have a rear wheel nut they wouldn’t have let me go back out.”

Even 63 years on, Hargreaves maintains that had he prepared the bike himself he wouldn’t have had these mechanical problems. “Tyrell Smith and Ernie Nott – who were running the bike – should have given it to me to sort out myself.

“I scared myself silly during that race with that wheel nut coming off, but in the heat of the battle I just cracked on with it. I had massive hand blisters afterwards and bleeding knees. I didn’t shut the throttle at any point and that made for a very hairy ride.”

He was, to put it bluntly, flying. Even travelling marshall Allan Jefferies said that Hargreaves was the quickest Clubman racer on the course.

All the excitement and vigour of this tale is matched by Hargreaves’ charisma and animated delivery, punctuating his racing stories by leaping out of his seat to demonstrate something. His notes are no different.

Written on the opposite page of his account of the white-knuckle TT victory he writes – in huge capital letters:

“ADDING GOOD PERFORMANCE BITS TO A NONE-PREPARED VEHICLE IS LIKE FEEDING STRAWBERRIES TO A STARVING PORKER. I ENJOYED RACING ‘OWN PREPARED’ MACHINES.”

This was Hargreaves’ last TT. But it was far from the last of his excitement…

Later that year Hargreaves started working at Rolls Royce, Barnoldswick as a methods production fitter with the turbine aero division.

“I was picking up jobs that were otherwise lagging behind but the trouble was that I would go home and I would be crying in my sleep – my eyes were constantly watering.

My GP, Dr Rutherford, said it was the vapour from the Mercury in the lights. He said: “You can’t work there anymore – it won’t do for your eyes.”

Rather than simply shifting jobs and staying in the same place, Hargreaves upped sticks.

So his next move was not just another job, but a 4000-mile move to Canada.

“I thought ‘okay, I’ll go to Canada because I’d read a lot about Canada’.”

His father had also moved there working on the St Lawrence Seaway. “Joe Guest at Rolls Royce said ‘go to Montreal’ but I read all about Montreal and didn’t like what I had read so I thought ‘I’ll go to Vancouver.’”

The plan was for Hargreaves to settle with a job and accommodation so that his family could follow. “I got this job working at a pulp and paper mill as an engineer, but I couldn’t find anywhere for them to live.

“I couldn’t even find us a big caravan so I had to quit and go back into town to find another job.

“They were advertising for platers at Burrard Dry Dock shipyard and there’s a hell of a difference between a shipyard and Rolls Royce, but I thought ‘third angle projection drawings, just the same as Rolls Royce, I can do it’ so I went there and designed the engine seating on a new ship, an icebreaker called the CCGS Simon Fraser.”

But safety at the factory was lax.

Above Hargreaves’ desk were huge pulleys transporting enormous components. “I spotted that the tags with the date on, by which the pulleys had to be tested, had long expired so I left.” But working at the dry dock did prove a valuable training ground.

While he was there, Hargreaves had started experimenting with reed valves in 40bhp two-stroke marine engines. This work, in particular, would come to define Hargreaves’ role in motorcycle race engineering, but more of that later…

Hargreaves’ transport at the time was what he calls a ‘Puddlejumper’ – an English Ford Anglia – but he could no longer drive with a British licence. “I had to get a licence for British Columbia – you had to get a licence for each province in Canada.

“So I went along for my test and I was sat there reading all the bloody answers from a book and there’s this German bloke opposite me who said: ‘You can’t do that’, so I said: ‘I’ve been driving for years. I’m not going through all this again’, so he said: ‘Pass us that book here’, and he started copying them out.”

The practical test was more of a challenge. “You had to call this number to book a car in which to take your practical test so I did that and this huge car pulled up – it had these enormous wings on and I thought ‘bloody hell’.”

The examiner passed Hargreaves on the grounds that he sounded like the 1950s film star Robert Donat, whose film Cure For Love was set in Salford. “He said: ‘I have just seen that film with Robert Donat called Cure for Love and you speak just like him’. I said: ‘Are you going to pass me on that ground?’, and he said ‘yes.’”

Armed with his licence, Hargreaves then got involved with air sea rescue for the US Air Force. “I was a station chief at a radar station near Hershell Island, an island off the North Sea.”

It was quite a culture shock compared to Clitheroe. “I went there on a snowmobile with a couple of Eskimos. We had stables for the horses and kennels for the huskies and there were only four of us there along with two Eskimo families.”

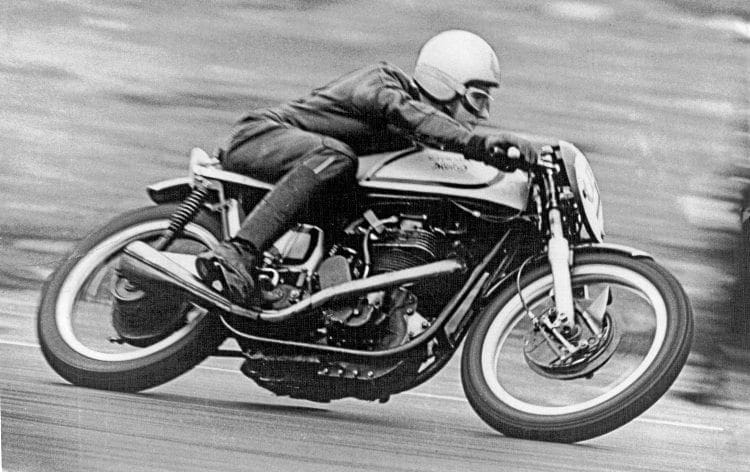

But in spite of adverse living conditions, the money was worth it. And it was during this time that Hargreaves became involved with the construction of Westwood circuit, near Vancouver. Hargreaves also bought a 500cc Manx Norton, which he named ‘Excalibur’.

Hargreaves had a whopping 11 wins out of 13 starts on his Norton, results that encouraged him to take his racing further afield – to California.

In 1960 Hargreaves started racing at the then newly built Willow Springs, Los Angeles, where his TT racing victory proved popular with the Americans, and the young radar engineer from Clitheroe was soon splashed across race programmes and pamphlets.

He said: “It was brilliant. They loved the fact I had done the TT – that was a huge deal over there. I entered 13 races at a new circuit called Westwood and insisted on helping to clear out the trees to get the track ready.

“I competed in the first US-sanctioned FIM motorcycle race near Bakersfield.”

Indeed, Hargreaves’ collection of literature bolsters the impact he and his racing legacy had on budding road race fans over the pond. “This picture here is a Country and Western singer called Spade Cooley.

“And that’s me with Miss Rosamund,” he said, leafing through a huge stack of photographs.

There’s even a piece in the Antelope Valley Press with a huge picture of Hargreaves accompanying the headline: ‘Huge Crowd Forecast for Springs Course’ and a caption that describes Hargreaves as ‘one of the top Canadian racers entering the first international GP motorcycle races at Willow Springs today’.

“They really wanted me to lead the development of their racing circuit,” he said. “It was quite a big deal, and I wanted to, but my wife Isobel wanted me to move back and she didn’t want to move to the US.”

So, in the early sixties, Hargreaves moved back to the UK and became a publican in Padiham, Burnley, and then Bury. For almost all of the 1960s Hargreaves was busy earning his bread and butter and looking after his family.

But towards the end of the decade he returned to his ideas about reed valves, devoting all his spare time to developing what would become a pioneering application.

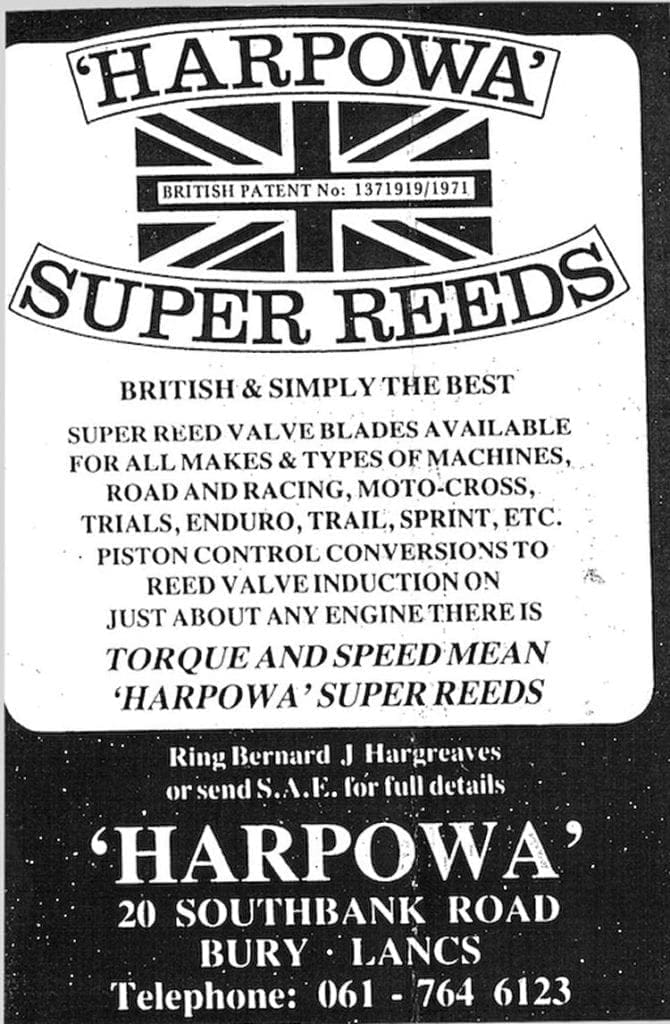

The burgeoning two-stroke Japanese motorcycle race market proved fertile ground for developments such as Hargreaves’ reed valves, and in 1971 he filed a patent for one.

It was around this time that he tuned a factory Greeves for Wigan-based scrambler Dick Clayton. “It went like the proverbial off the shovel,” says Hargreaves. “

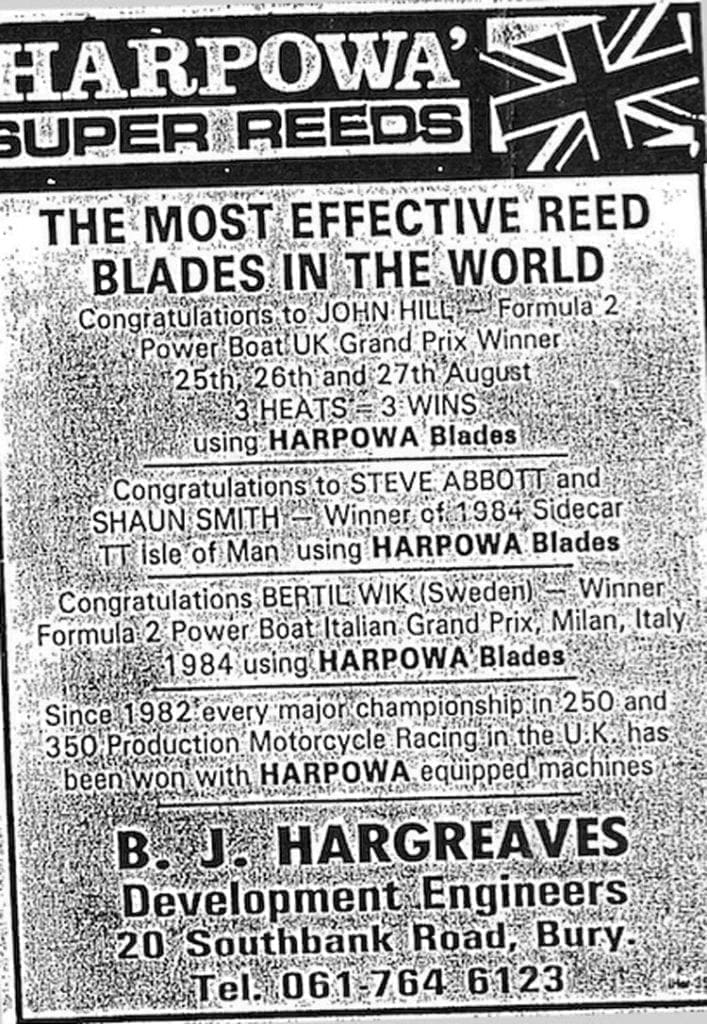

In 1982 Hargreaves was able to give up his day job as a publican and set up his reed valve engineering business, Harpowa. Indeed, an advert for Harpowa proudly lists Hargreaves’ achievements: ‘The most effective reed blades in the world’ and then lists its victories, among which are a Formula 2 Power Boat Grand Prix winner ‘every major championship in 250cc and 350cc production motorcycle racing in the UK’.

But as two strokes started to lose their popularity, Hargreaves started applying his engineering knowledge in other areas.

One such area was working for Kenny Roberts’ race team, for which Randy Mamola was riding. “Mamola was struggling push starting his motorcycle because he was short like me so I got the motorbike – pretty big piece of kit – and I’d run with it for two yards, bump on the seat, knock it off, run with it, knock it off, run with it for another couple of yards…

“So I was going along, running two yards, dropping the clutch, starting it, knocking it off, running another two yards, I was starting and stopping it so that cured that.

“But shortly after that they decided they weren’t going to start them with dead engines, they were going to start them with the engines running and I think Kenny Roberts had something to do with that because of Mamola – along with other people having the same problem as well.”

He was also asked to work as a consultant to Cagiva, with the aim of increasing the performance of the 125cc single-cylinder engine by a minimum of five per cent in a range of 3000 rpm.

“Cagiva took me on all sorts of trips,” says Hargreaves, “including one to Italy in which they took me to see motorcycle designer Tamborini’s workshop. They also wanted to take me to see Renzo Pasolini’s grave but I said I was busy trying to avoid my own funeral.”

Indeed, it’s Hargreaves dry wit, sheer resilience and straight-talking sensibility that has permeated his racing career, his stint in Alaska and later, his reed valve work.

After all, there aren’t many people who can ride the mighty Mountain course without a wheel nut.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicracer.com and in the May/June 2020 issue of Classic Racer – on sale now!