The Rickman brothers’ Metisse motorcycles found success on both dirt and road racing stages, while their sporty road offering was a splendid piece of kit too.

Words: ALAN CATHCART Photographs: KEL EDGE

Britain’s illustrious Métisse motorcycle marque was founded in the 1950s by brothers Derek and Don Rickman, off-road aces and household names in Britain thanks to terrestrial television showing the scrambles racing in which they excelled every Saturday afternoon in winter.

After achieving dirt-bike dominance with their stiff, good-handling frames, powered by British twin and single motors, they then did something comparable with road bikes. Rickman went on to briefly become Britain’s largest road-going motorcycle manufacturer after the demise of Norton first time around, and before John Bloor resurrected Triumph.

The Rickmans’ creations not only represented a key stage in the evolution of the modern off-road motorcycle, they also played a role in helping the Japanese manufacturers discover the black art of frame design for their four-cylinder roadsters, in making Hondas that handled, and Kawasakis which delivered their impressive horsepower to the ground, without trying to chuck the rider off in doing so. It’s fair to say the brothers’ bikes changed the face of modern motorcycling, even if it’s too little appreciated today by exactly how much.

That process began with the creation in March 1966 of the first tarmac-focused Métisse chassis, after the Rickmans were approached by leading road racing sponsor Tom Kirby to design and build frames to accommodate AMC’s Matchless G50 and AJS 7R motors. Bill Ivy took the Kirby Métisse G50 to victory in its very first race at Brands Hatch that spring, the first of exactly 999 such frames in total made for twins and singles, according to the surviving, handwritten Rickman factory record book of Métisse frames built throughout the company’s history. A trawl through this reveals many fascinating pieces of trivia, as well as representing a who’s who of motorcycle sport.

The Kirby Métisse road racers all featured the unique conical-hub disc brake which became a trademark of 1960s Métisse tarmac frames, based on a much heavier American design which Kirby’s South African rider Paddy Driver had brought back to England from racing at Daytona. An AJS-engined Kirby Métisse 7R soon followed for the 350cc class, in which it duly competed against the even lighter Aermacchi Métisse, built in collaboration with British importer Syd Lawton, whose Southampton dealership was close by the Rickman factory. But, inevitably, the next step was to make road bikes.

The first complete road-legal Rickman Métisse duly appeared in November 1966, built to accommodate a Triumph T120 engine for delivery to Austrian importer Otto von Arx. Rickmans always sold well abroad, and a certain Giacomo Agostini even bought a 650cc Triumph-engined Metisse café racer in April 1968 with frame no. 227, to ride on the streets back home in Bergamo.

But demand for the frame kits for street use, generated by the well-publicised success of the Kirby machines in the hurly burly of British short circuit racing of the day, was rather spasmodic, since, according to Don Rickman, there wasn’t any real effort to promote sales of the Street Métisse kits until the demise of the brothers’ own road racing project, a Triumph-engined Métisse frame with the 650cc Bonneville motor bored out to 683cc, and fitted with an eight-valve cylinder head designed for them by Harry Weslake.

“Alan Barnett and Rex Butcher rode it for us, and did okay with it,” says Don, “since with the extra capacity and the eight-valve head it was producing about 70 horsepower, whereas the standard Triumph gave out 47bhp. But the crankshaft wouldn’t stand that, so we had to pack it in. We were left with a nice little racer with a Triumph engine – so why not put lights on it to make a café racer, which was all the rage just then? So that’s how it all got started properly, in 1968.”

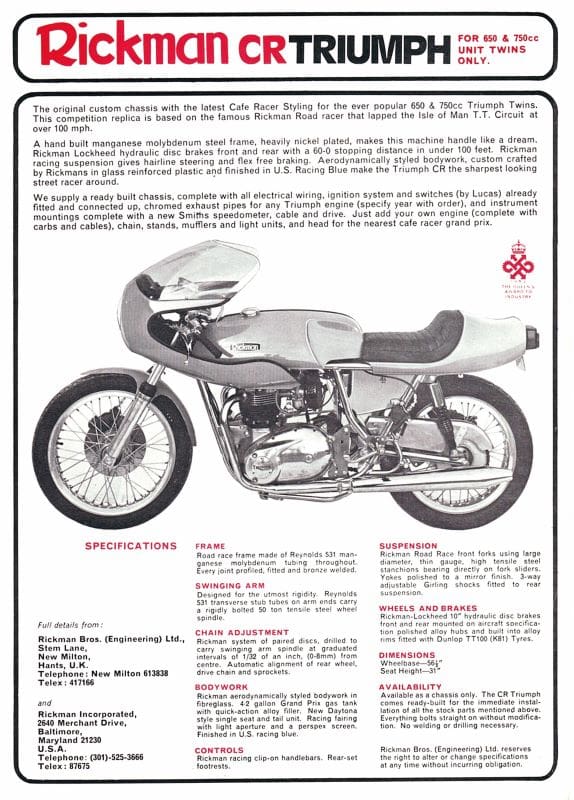

Normally, though, the Rickmans initially only supplied frame kits, as none of the major British motorcycle manufacturers would sell separate engines to them. “The British factories were completely uninterested in what we were doing, and would never supply us with anything,” Derek Rickman told me before he passed away last year, aged 88. “Not wheels, not forks, nothing – not even cash on delivery, not even after we’d become established, and to be honest, rather successful. As demand for our Street Métisse frame kit for the 650cc Triumph T120 motors grew, we tried to obtain supplies of this engine to build compete motorcycles, but sadly we were repeatedly turned down by the bosses at Meriden. With a very few exceptions, we could only supply customers with Rickman CR [for Café Racer] frame kits – and even the fully built-up bikes we supplied to people like Ago entailed purchasing a complete motorcycle just to obtain the engine unit.”

But despite this obstacle the introduction of the Street Métisse CR frame kit in 1968, promoted by a vigorous advertising campaign, saw sales leap ahead, so that by the time production of the twin-cylinder kits ended in 1974, the Rickmans had produced 856 such frames in total, more than 50% of which housed Triumph engines, including 81 Police versions. The first of these was built in January 1969 for the local Dorset force, who used it for fast patrol work, followed in August that year by a single test example for West Mercia Police. By 1973 the Rickman Triumph Police Métisse was being used by several forces from Hull to Bristol, Hampshire to Bedford, with the bikes proving popular with patrolmen because of their excellent handling, outstanding braking, and rider comfort. The West Mercia force even specified the more powerful Weslake eight-valve conversion kits for their machines, which increased power from 42bhp to 65bhp, with extra torque, too, thanks to an engine bored out to 683cc.

“The cops rather liked having bikes with quite a bit more power than the average lad could buy!” Derek Rickman once laughed. The same frame design was then adapted to house four-cylinder motors, firstly from Honda and Kawasaki, then later on Suzuki, with production continuing until 1985, by which time a grand total of 2057 such frame kits had been made. “When we started fitting the Honda four and the Kawasaki Z1 motors in the frame, that really stopped Triumph sales, because everyone wanted the four-cylinder job,” says Don.

SAMMY MILLER MUSEUM

There’s more than 400 fabulous motorcycles in the Sammy Miller Museum, including these two Metisses, here with Sammy. The museum – open daily from 10am – is at Bashley, New Milton, Hampshire, B25 5SZm telephone 01425 620777 or sammymiller.co.uk

The Street Métisse triangulated duplex frame was entirely sift bronze-welded using Reynolds 531 chrome-moly steel tubing exclusively, because back when the brothers were just getting started, before designing their very first frames they went to the Reynolds company and talked to master welder Ken Sprayson. “In those days, he was the whizz kid for frame construction,” says Don, “and he showed us all the technical stuff, including his tricks of the trade. We never used anything else after that.” The frame was nickel-plated – another Rickman feature from first to last – with the firm’s own meaty-looking 1⅝-inch/41.3mm telescopic fork set at a 27.5º rake in Rickman’s forged triple-clamps, with 5in/127mm of wheel travel. The sturdy front end was required because of the cast iron front disc brake fitted, on some models combined with a rear disc as well, for the first time ever on a production bike.

“Our road racing entrant Tom Kirby came to us with a big cast aluminium hub to house a disc brake in which his South African rider Paddy Driver had brought back from America, and said, ‘Can you do something with this?’” recalls Don, “So we had to develop our own forks to use it, because it needed a caliper bracket on one side, and it all went from there. We’d started using the front disc with Matchless forks, but these were never strong enough to absorb the braking forces without deflection, so that’s why we went to 1⅝-inch tubing, to prevent that.

“Dare I say it, we were the first people to go to the big tube forks, because we found that with a Lockheed cast iron disc brake which worked much better than the steel one Honda used on the CB750 four’s front wheel, you needed something sturdier to withstand the braking forces. And to go up to 1⅝-inch [41.3mm] diameter from 1⅜-inch [35mm], that makes a tube much stronger. Plus, we had our tripleclamps made out of some very high-grade alloy material, the same as the factory we got to make them for us in France used on the Caravelle aircraft undercarriage they were then making parts for. Our head crowns were forged, too, not cast, which made them a lot stronger – we never had a tripleclamp bend, ever, not even with the worst of impacts off-road.” After the first seven bikes, the large US-sourced front hub which was also quite heavy, was replaced by Rickman’s own much lighter cast aluminium hub.

The tubular steel Métisse swinging arm carried twin Girling shocks, but featured a hitherto unique means of chain adjustment for the first time ever on a series production streetbike, via an eccentric swinging arm pivot. “What we really set out to do on all our frames was to make the back wheel follow the front one exactly,” Derek Rickman once explained to me. “So what we had to do was clamp the rear axle strongly in the swingarm, and alter the chain adjustment at the frame pivot, which made it very rigid. We had to design the steering head so that it held the forks very rigidly, via our own forged triple clamps and bigger diameter fork tubes, which were very strong, so you wouldn’t get any whip at all. Then from the steering head to the swingarm, the frame had to be such that it wouldn’t twist in any shape or form. Also, as long as you used the same discs on both sides, the braking forces would always be in line as well, so wouldn’t affect the steering.”

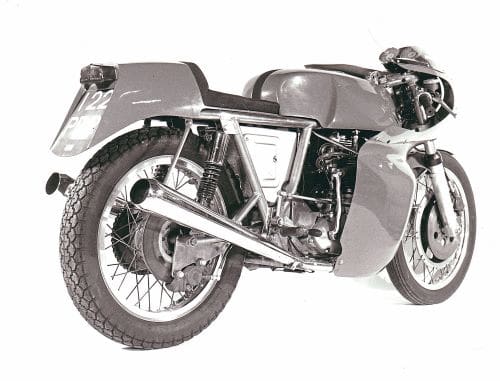

There’s been quite a high survival rate of the 450 or so Rickman Métisse CR Triumphs built up in the 1970s, although the one that very appropriately is on display in the Sammy Miller Museum sammymiller.co.uk on England’s South coast isn’t entirely what it seems. Appropriately, because the Rickmans were the reason that the multi-skilled Ulsterman moved to the area as long ago as 1964. Sammy explains:

“My association with the Rickmans started because of Bultaco,” he says. “After giving up Grand Prix road racing with Mondial in 1957 [in which he finished third in the 250cc world championship, and fourth in the 125cc class] I began working at Ariel’s in Selly Oak, Birmingham, competing in trials and the ISDT on bikes I was developing for them. By 1964 things in the British motorcycle industry were already pretty bleak; BSA had closed the Ariel factory at Selly Oak in 1962, and moved production of the Leader and the Arrow to the BSA factory at Small Heath. BSA guys didn’t like Ariel guys, and Ariel guys wouldn’t work with BSA guys, so it was a total joke, plus I was blowing all the BSA trials aces off each weekend with GOV 132 [Miller’s legendary white Ariel HT5 mount] which went down a bucketload with BSA management, so they were hell bent on stopping Ariel doing any more competition.

“So the warning bells were there for me to move to Bultaco at the end of 1964 to develop a trials bike for them, which ended up being the Sherpa. But Señor Bulto said it would be sensible for me to move to New Milton to join the Rickmans, who were his British importers, to help develop the Sherpa by having a workshop of my own there to sort out any problems. I duly moved to New Milton, and the old Rickman factory was less than a mile from where the museum is today!”

Despite which, until 2011 there was no Rickman Street Métisse in the museum, a gap which Sammy resolved that year by purchasing a derelict ex-Mid Anglia Police bike built in November 1973 and carrying chassis no. 1353, which he‘d been offered. “A chap called Wesley Harris rang up from Portland Bill, which is a pretty remote stretch of coast,” he recalls. “He says, ‘We’re moving house, there’s a Rickman in the shed. Do you want it?’ So off I go down to Portland Bill, to arrive at this little cottage with the Rickman in a shed in the garden. It’s been pretty well weathered, but we agree a price – however, there’s a big stone wall built right around the garden which we had to dismantle to get the bike out of the premises! Eventually I came back with it in pretty rough shape, but basically all there.”

Together with Bob Stanley, the Miller Museum’s mechanical magician back then, Sammy duly refurbished the Rickman Police bike, and in so doing transformed it into a Café Racer – the frames are identical, except for two additional frame tubes on the Police version to support the walkie-talkie radio, which he simply removed before replating the frame. Gerry Lisi at Métisse Motorcycles still offers the CR Métisse frame kits, so he supplied all the new glass fibre parts necessary in a fetching shade of British Racing Green. Quite apart from its performance, the Rickman Triumph is eye candy at rest – long, low, lean and lithe, with sweptback exhausts either side adding to its rakish appearance, it looks a million dollars, and certainly the epitome of late-1960s/early-1970s British café racing design.

Both wheels are 18-inchers, fitted with a new second-series Rickman 8in/203mm cast iron front brake disc with single-pot Lockheed caliper, matched to a same-size Triumph SLS rear drum. The Akront alloy rims are shod by Mitas tyres which heated up pleasantly quickly in the course of a ride out into the New Forest lanes surrounding the Miller Museum’s idyllic location – though it took a while to persuade the Triumph motor to fire up for the ride. You have to fold back the right footrest in order to kick the Triumph into life, which I’ll admit took quite a bit of practice, although the fact there’s just a single 30mm Amal Concentric carb – no room in the frame design for a twin-carb Bonneville cylinder head – may have been an issue here. But eventually I coaxed it into life, letting it settle down to a fast-ish 1200rpm idle speed before notching bottom gear on the one-up right-foot gearshift, then hearing the distinctive dull thud of the trademark 360-degree British parallel-twin motor as I accelerated off the mark with surprisingly little work needed by the light-action oil bath clutch to get this show on the road. And it is indeed a glorious show – this motorcycle looks like it’s doing 180mph just standing still – or so it seems.

Fitted with an eight inch cast iron front disc gripped by a single-piston Lockheed caliper, the Rickman Triumph weighed in at 365lb (166kg) dry, a massive 49lb (32kg) lighter than a stock 1973 Triumph Bonneville with its inch-shorter (by 25mm) 56.5 in/1435mm wheelbase. Besides the lighter frame and brakes, those 18-inch Akront alloy rims saved significant extra weight, unsprung at that, while the breadloaf-shaped 4.20 Imperial gall./18.66 litres fuel tank, as well as the base of the long, flat seat with slightly raised passenger space, were all made in glass fibre at the Rickman factory, with the seat pan extending back to comprise the tail section and rear mudguard. At 31in/787mm the Rickman’s seat height wasn’t too cramped, and the quite high-set footrests were reasonably accessible for a 5ft 10in tall rider like myself. But the riding position is pretty stretched out, with a L-O-N-G reach to the quite steeply dropped clip-on ’bars.

The Rickman’s great forte is its rock-solid handling and completely predictable steering, which allowed me to make the most of the good grip provided by the front Mitas tyre in keeping up turn speed. The chassis felt pretty well-balanced and confidence-inspiring, with the sturdy-for-those-days Rickman fork adequately compliant and well-damped. The twin Girling shocks were pretty taut, though, and the Métisse skipped in the air a little over the worst of the surfaces we found running along New Forest back roads, but by the standards of 1970 this is a capable motorcycle. However, besides the fact that the front brake lever was extremely short – why? – the front disc brake didn’t have as much bite as I expected, with a very wooden feel in terms of lever response. I know how well that Lockheed caliper can function from all the years I’ve been racing with one on my 750SS Ducati gripping a Brembo cast iron disc – though the rear drum thankfully worked much better. Might different pads cure it, maybe?

Métisse is the French word for ‘mongrel’, in two-wheeled terms denoting the combination of a proprietary engine in a Rickman-built frame. But this Triumph-powered roadburner seems a whole lot classier than that epithet denotes – it’s a fine example of the Rickman brothers’ chassis expertise, which epitomises the refined design ethos and the improved handling the Métisse frames delivered, coupled with sensational good looks and a real sense of quality of manufacture. That’s hard to beat.