The Oxford English Dictionary describes symbiosis as “an interaction between two different organisms living in close physical association.” Some motorcycles are like that. They feel like living things and become an extension of the rider. And the rider can feel as if they have become a part of the machine, to create a single collective being.

With a lot of 1950s and 1960s British motorcycles, the relationship between the rider and the machine follows a pattern. “Here I am,” say these motorcycles, “sit on me, start me, and I will try to take you to your destination.”

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

On the Triumph Speed Twin, things don’t work like that. The relationship between the pre-unit Triumph and the rider is symbiotic. “Here I am,” says the Triumph. “Do you want to go and have some fun?” And you quickly become a part of a whole; a single organic beast. Each move of the body in the saddle, each lean into a bend, every tiny noise is part of a shared experience. There’s a joyous feeling of life affirmation. If it could, the Speed Twin would wink at you.

It is an undeniably attractive motorcycle, the Speed Twin – proportionally perfect in every way. The Triumph that Pembrokeshire Classics have kindly let us have a go on had acquired a single mile to add to the 69,000 already on the clock since a full engine rebuild. As such, it was very much in the running-in phase.

Owner Alistair pushed the bike into the sunlight, turned the fuel on, gave the carb a tickle, and applied a firm prod to the kickstart. It started unfussily straight away and quickly settled down to a gentle tickover.

‘It started first kick’ is a bit of a cliché when dealing with bikes from this era, and often fails to mention that before that first kick there’s a lot of faffing about to do. But with the Speed Twin there was none of that setting the manual/advance retard, finding TDC, pulling on the decompressor, giving it a long swinging kick kind of nonsense. On the Triumph you just kick it and off you go.

It must have been a revelation back in 1957 to climb on your bike and just start it. You can see why the Metropolitan Police bought so many. You don’t want a traffic officer sweating away in his gauntlets and greatcoat trying to start a recalcitrant machine while a miscreant powers their speeding Jaguar over the horizon.

The Speed Twin was a small bike for a 1950s 500, which adds to its charm. This sparseness of construction helps these compact machines look eager and ready for action.

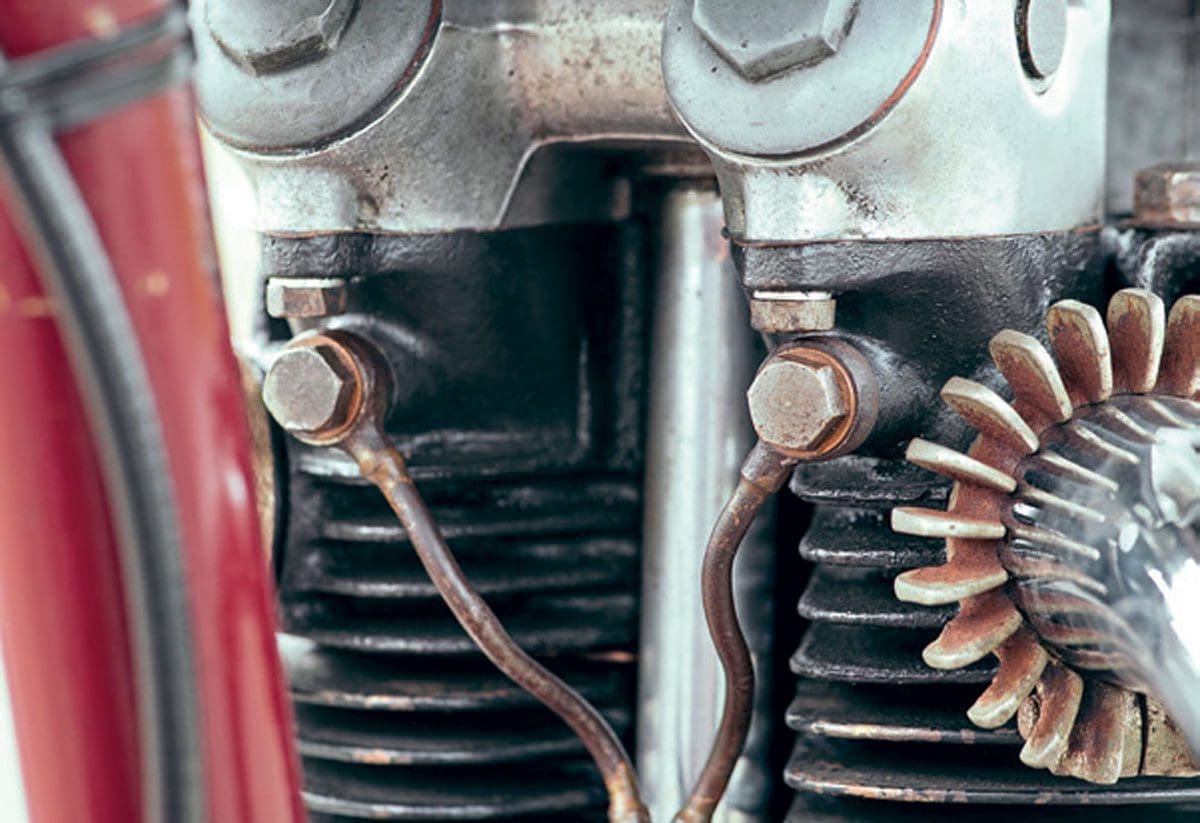

The engine rustled away, the cast iron barrels and head contributing to the lack of engine noise, though this could be down to the superb job done on the engine. I’ve had mechanically noisier water-cooled Suzukis.

Before engaging first, I took a moment to acquaint myself with the machine. Sitting in the saddle, the Triumph doesn’t feel that far away from a modern bike. The right-foot change goes the modern way – one-down-three-up, Triumph-style. A modern rider with no experience of a British classic could get on the Triumph and, apart from a moment to get used to the gear shift, would feel at home straight away.

The Speed Twin’s instrumentation is basic, with the usual Smiths Chronometric speedo, ammeter and on switch, a dip switch and a horn. It even has an ignition key, something less common than you might think. So, with the engine started, just pull in the clutch, engage first and off you go. Unlike some older Triumphs, there was no crunch from the gearbox; rather, it snicked silently into gear. This is, one suspects, down to the recent rebuild. One of the main reasons Triumph gearboxes crunch is the tendency for clutch plates to stick together if the bike is left standing.

There is not a lot going on to distract you from the ride – and the ride is the thing with a Triumph. A short run gave the little Triumph a chance to stretch its legs and wag its tail a bit, but in deference to the recent engine work, the journey was gentle.

Getting rough on a first acquaintance is never appropriate. The riding position was one of the most comfortable I’ve come across. The low seat height was a boon to weary bones that have atrophied a little over the winter, and it was a comfortable fit. The Speed Twin has 19-inch wheels front and rear, which makes the low profile quite an achievement.

The twin seat on the sprung frame was also used on the sprung hub models; first as an option and later as standard equipment. It was surprisingly comfy and sloped downwards to give a great riding position. Handlebars are flattish and the footrests are more forward than most, making for a relaxed riding position.

For the first time in an age, the combination of seat height and bar height gave me a low profile that allowed me to turn my head and look behind. I quickly saw why the Speed Twin was popular with tourers and those police officers who were in the saddle all day.

The forks are forks. They go up and down and are primitive but functional. Edward Turner’s obsession with low weight gives the Triumph the ability to accelerate at a rate that makes it more than capable of keeping up with modern traffic, if you must – though let’s be honest, who wants to do that? That’s not what the experience is all about.

‘Everybody’ knows that, apparently, Triumphs from the late 1950s have a reputation for poor or at least unpredictable handling, but it didn’t seem to apply here. One wonders if back in the day the reason people complained about the handling was that they were used to solid and ponderous steeds, which is something the Speed Twin definitely isn’t.

Perhaps inexperienced riders on worn-out twins ragging them furiously down a by-pass in the 1960s might have found it a bit skittish, but that’s not what a Speed Twin is for today. Down deserted back roads, the Speed Twin chuckled onwards.

The brakes were astonishing – 1950s stoppers, like Triumph frames, don’t have the best reputation. On this bike, with the larger front brake and its air scoop on the front, which was an option normally seen on T100 production racers, the Speed Twin could be quickly brought to a halt. Combine it with a dab on the back brake and the brakes curtailed forward movement in an impressive fashion.

Great in the countryside, the brakes would be usable round town, even where the modern rivals for road use are all ABS equipped.

After a ride of charm and distinction, like all good things it had to come to an end, but this was one of those motorcycles that the rider was reluctant to return to the shed. Just one more blast, please.

If anyone offers you a ride on a pre-unit Speed Twin, seize the opportunity. It’s not something you will regret.

He came up with a powerplant some claim to have been derived from a Riley car design, which also featured hemispherical cylinder heads, valve timing set at 90º, short rockers and twin camshafts situated fore and aft.

With the Speed Twin, Turner created a concept for a motorcycle engine that was to be the backbone of Triumph’s production for the following five decades, and looks that have lasted well into the 21st century.

Turner’s genius for marketing as well as design saw the creation of a machine that, at a quick glance, looked more like a compact twin-port single than a twin so as not to frighten the traditionalist buyers, and he designed the original engine to be built on the same production lines as the company’s singles, too.

His marketing nous allowed him to recognise that to sell more motorcycles, his new twin didn’t just have to be fast – it needed to look good doing it, even if this was at the expense of handling.

Turner’s philosophy was: “Using the minimum amount of metal for the maximum amount of work.” This made his bikes a little more fragile, but also lighter and faster; a trade-off that has been part of motorcycle design ever since. The Speed Twin was also cheap, costing just £5 more than the aging single cylinder Tiger 90.

Stylistically the twin changed as the years passed, as you might expect. The chrome tank panels on the early rigids and sprung hub models gave way to all-over Amaranth Red, a colour selected by Turner’s wife, who grew Amaranthus Love Lies Bleeding flowers in their garden.

It lost its tank topping instrument panel in the late 1940s, gaining instead the small tank parcel rack, the design of which was popular with some but also put fears of vehicular castration into the heads of some male riders.

In 1949 the Speed Twin gained Triumph’s signature headlamp nacelle, a large steel pressing that held the instruments, horn, and headlamp that became a signature part of the design into the mid-1960s. In the process it lost the oil pressure gauge, which was replaced by a small mushroom-shaped plunger that stuck out of the pressure relief valve.

This all helped the engine turn out 26bhp and the first models could manage 90mph. Or 94mph. Or 100mph, depending on the journalist’s imagination and who had prepared it at the Meriden factory. The bottom end was so well-designed that Triumph was able to punch the engine out to 649cc without much issue.

In 1953, the Speed Twin engine’s electrical arrangement was one of the first fitted to a British motorcycle to reject a generator and magneto in favour of an alternator, battery and coil set-up. The distributor was behind the cylinder block in the place where the magneto had been located, with the coil mounted on top of it, which made it hard to get to the contact breakers.

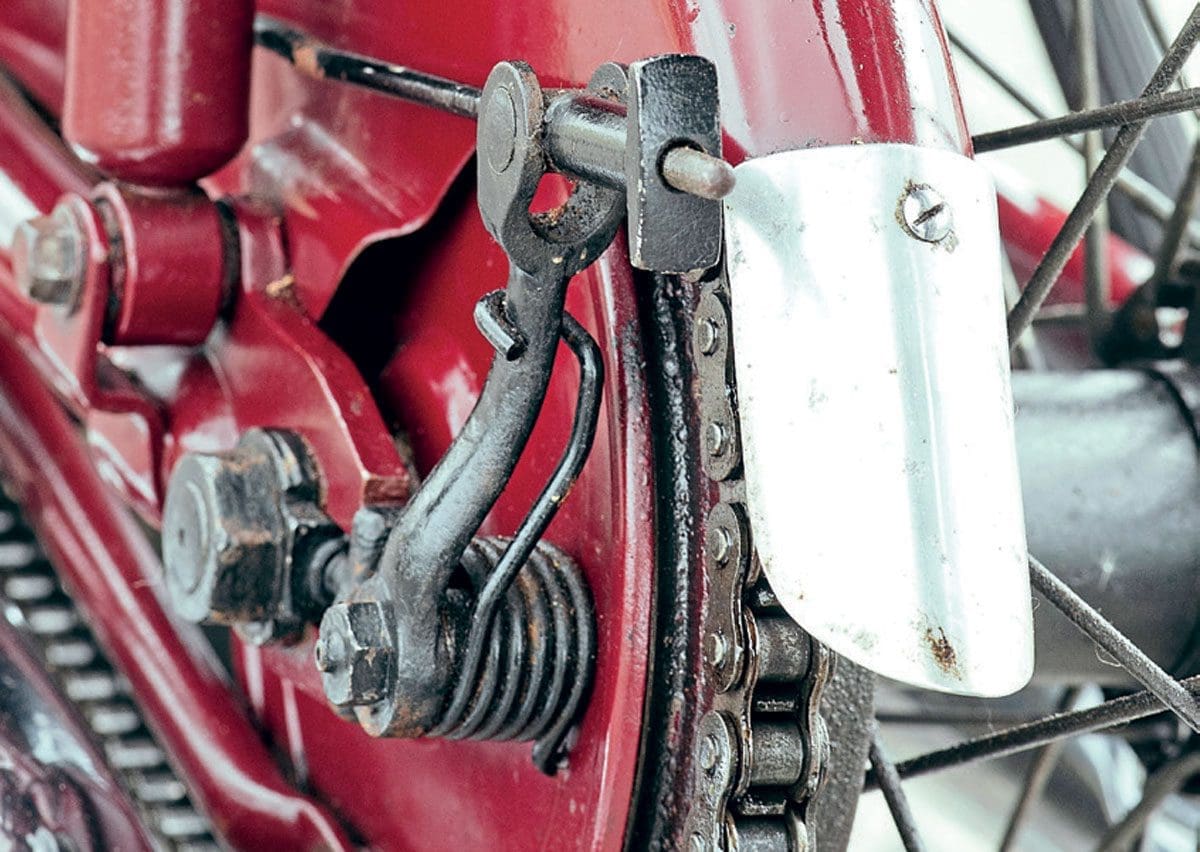

The alternator was on the left-hand end of the crankshaft under the primary drive casing rather than being stuck on the front of the engine like the previous dynamo, which required a change in the design of the clutch to accommodate a shock absorber. The gearbox was attached to the frame by a bolt through the lower lug on the frame, with an adjuster bolt above the gearbox.

In 1954 it was sold for the first time with a swinging arm frame, Triumph being a little late to that party. As the bikes got older, some riders felt it had issues and it was criticised for being not terribly stiff.

The design featured a new bolted-on rear subframe holding the seat and rear suspension rather than a single chassis. Full-width aluminium brake hubs arrived in 1957. While often derided, Triumph persevered with the bolt-on subframe and the same basic design concept, strengthened and updated over the decades, was used into the early 1970s, ending its life on the Triumph Trident T150.

A significant part of the frame design was the use of the 3½ gallon petrol tank as a strengthening member to stiffen up the top frame tube.

The “bathtub” bodywork, loved by the motorcycle press, meant the 5TA Speed Twin could be “washed down in less than 15 minutes”, reported one tester. But this was one of those occasions when a manufacturer should have ignored the press and asked the riders what they wanted. The bathtub arrangement was a huge turn-off, not just in the UK but also in the all-important US marketplace. Dealers there would simply take the panels off and discard them.

The 5TA was fitted with 7.0:1 pistons and produced 27bhp at 6500rpm, only slightly more than the rigid-framed original. The machines were still finished in Amaranth Red.

Triumph mucked around with steering geometry, brakes and exhausts, ditched the distributor in 1964 and relocated the points to the timing chest. The bathtub shrank and was then dropped, and a bolt-on top tube which could be retro-fitted to earlier machines dramatically improved the rigidity.

When the Speed Twin was finally discontinued in 1967, the famous nacelle – a marque feature for nearly two decades – went with it and the Speed Twin name finally vanished… until 2020, when Triumph revived it for a 1200cc retro-sporting behemoth.

Monty at Monty’s Classic Motorcycles says the 12v positive earth Zener diode is no longer available but that a solid-state regulator/rectifier will do the job. The four-speed gearbox can be crunchy. This is almost always down to a worn clutch. Care and attention to the clutch arrangements and regular use will solve a lot of these problems.

“If the clutch is dragging or worn out, that’s where you will get problems with the gear change. The actual gearbox is bulletproof, as long as it’s got oil in it,” said Monty. Most of the engine internals, gearbox components and clutch parts are available off the shelf. “As long as you have crankcases, crank, barrel and head, you can get everything else,” Monty added.

If the greasing of the swing arm pivot has been neglected, the bushes and swing arm can wear badly, then seize, requiring the owner to take on the tough job getting it out and replacing it. As the pin is an interference fit, the way to get a seized pin out is to completely strip the frame and use a press.

“Sometimes people have tried to do this with big hammers and bits of metal. This is where you will find problems,” Monty said. “Give the pivot a few good pumps of grease once a year. You can get all the parts for the pivot if you have to replace it.”

You need to watch out for the shock-mounting bushes wearing and the shock absorbers then rubbing on the swing arm and top frame mounts.

Triumph’s twin seat is much more comfortable than a lot of those fitted to bikes of the period.

The Amaranth Red paint scheme was a stand-out feature in the days when black and occasionally chrome were the normal finishes for a motorcycle. It came in several shades, however, and one Amaranth Red Speed Twin can look quite different to another.

Monty’s best advice is to get your hands on the right owner’s manual for the model and use that rather than trawling the internet for information.

“There are two factory manuals – one for all pre-unit twin models, 1945 to 1955, and one for 1956 to 1962. The Haynes manual will tell you a lot of what you need to know, too,” he said.

Among the more entertaining claims from Triumph’s advertising in the early 1950s was that the 500cc Speed Twin was thirstier and more likely to use up your fuel coupons than the bigger 650 Thunderbird.

Despite being the progenitor of all the Triumph twins that followed, the Speed Twin lived in an unregarded backwater from the mid-1950s onwards.

In 1947, faced with a then sporty little 500, The Motor Cycle commented on how quiet, smooth and respectable the Speed Twin was. The publication waxed lyrical about the Triumph: “Given its head, the Speed Twin possesses all the performance normally useable on British roads. With silky smoothness it eats up the miles relentlessly in a manner that makes hard riding an utter joy. Its zestful, vibrationless power, excellently chosen gear ratios, good steering and road holding and first-class brakes are but some of the endearing features.

“The Triumph Speed Twin in its latest form well merits its maintained popularity as a high-grade product of which any rider would be proud. Moreover, exported as it is in large numbers to the various overseas markets, it is a worthy example of British motorcycle engineering skill.”