If you grew up in the 1980s and 1990s with inline four-cylinder bikes screaming, Bandits pulling wheelies, and loud end cans, the Kawasaki Z750 is one of the unsung examples. It’s a classic in all aspects of the meaning, and it’s cheap…

Words and pictures by Oli Hulme

This article originally appeared in the August 2025 issue of Classic Bike Guide

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

The big sellers in motorcycle showrooms during the late 1990s were not fairing-clad race replica sports bikes. Adventure steeds, or even retro twins, had yet to become mainstream. The bikes we saw the most of were mid to large capacity inline-fours. Bikes like the Suzuki Bandit, the Yamaha Fazer and Honda Hornet, and a few Kawasaki Zeds.

The theory was to make a bike that people could actually use on modern roads. And the recipe was simple: take a sportsbike engine from previous years, retune for less top end but more midrange power, lower the gearing, pop into a cheap-to-make steel frame with budget suspension, and keep prices low for maximum bang for your buck. They sold by the bucket.

Over time, as they weren’t anything special, they faded away from owners’ hearts. Today, 30 years later, these bikes are not just cheap to buy – you can easily grab a 600 Fazer or Bandit for less than £1000 – but they are also ‘classics,’ in the eyes of insurance companies at least, and one can sit happily alongside a Velocette on your multi-bike policy. And if the bike was made before 2001, the VMCC recognises it as a classic too.

For the classic rider, these ‘naked’ bikes can be well worth considering as an alternative turn-key ride, coming as they did before catalytic converters and ABS, but still offering a relatively sophisticated and reliable riding experience.

After being the first out of the traps with its most authentic-looking Zephyr range, by the late 1990s Kawasaki had largely missed the boat with its own naked fours, the biggest offering being the rather dull 750cc ZR-7. This had knocked around for the best part of a decade, largely ignored. It had the last iteration of Kawasaki’s twin cam air-cooled engine that had been born in the Z1 in 1972. The ZR-7 wasn’t a bad motorcycle, but it wasn’t massively exciting, or pretty either. Today, you would be hard pushed to spend more than £1500 for a ZR-7 compared to its smaller sibling, the ever-useful, reliable as a hammer and cheaper-to-run 500cc ER-5 twin, hailing from the GPZ500S. But that’s for another day.

So, in 2005, Kawasaki got busy. It gained a new chief designer, of Mazda MX-5 fame, who helped the resurgence of a Kawasaki brand that stood out. And, having been rather left behind in the biggish naked four-cylinder stakes, the team came up with the Z750. It was a smaller brother to the bonkers four-exhaust-piped Z1000, which in turn had been developed from the ZX-10R sportsbike. To keep the Z750 price down, it had a steel frame, a set of non-adjustable 41mm forks and simple preload and rebound adjustments for the old-style Uni-Trak system’s single rear shock. So far, so much like the ZR-7.

More inspiring upgrades included then fashionable lightweight six-spoke wheels shod with radial tyres (yes, oh young readers, this was still a good thing in the ‘90s), an anti-tamper ignition lock, decent but simple instrumentation, and an LED taillight at the back. The big difference was the new engine, a fuel-injected inline-four. The 748cc, liquid-cooled, 16-valve powerplant had elements from both the ZX-9R and more modern Z1000 and ZX-10R engines, with external looks improved. The 750 came with the same radiator as the Z1000 and many of the same dimensions as the bigger machine. Despite this, it was also cheaper than a Honda 600 Hornet.

The designers of the Z1000 had given it a stand-out love-or-hate 4-into-1-into-2-into-4 exhaust, but the 750 had a simple, if substantial, 4-1. The seat was an incongruous two-piece unit. The Z750 was soon joined by the more user-friendly Z750s, which came with a more substantial nose fairing and one-piece seat, making the bike more suitable for distance riding, if giving it a less aggressive appearance.

The Z750s on the road

The high spot of the Z750s is the engine, and what a fine thing it is. My normal frame of reference for a 750 is either my T140 Bonneville or ‘Guzzi V7, both pushrod twins, with the ‘Guzzi the more powerful machine at 47bhp. The twin cam Z750s motor produces more than twice that, a claimed 110bhp, though 25bhp less than the Z1000. This is a huge amount of power by comparison with my twins, and the way the Zed’s power comes in is fascinating. There is lots of smooth power at low revs, and if you want more, you just roll back the throttle and there it is, absolutely buckets of it. At those higher revs under acceleration, the exhaust starts to growl deeply, too, which is nice. There is a little more vibration apparent at those higher revs to remind you that you are shifting a bit. The engine is the thing that makes the Z750s shine.

The nose fairing on the Z750s works well with the bike’s relaxed sit-up-and-beg riding position, creating an impressive bubble of still air around your chest and dispersing the remaining air over the top of your crash helmet. This is good on long rides; however, the seat/footpeg/‘bars dynamic did take a little getting used to. The seat is low enough for the shorter rider – at 5ft 10in tall, I can get my feet flat on the floor with my knees slightly bent, so a taller 6ft-plus rider might find it a little cramped, even though the official seat height is 32 inches. The seat’s angle takes a little getting used to. If you stick your bum in the back of the rider’s perch, you put much of your upper body weight on your wrists, but if you slide forward you can seriously feel the bumps, as you are sitting over the shock absorber. Dabbing it about from a standstill can be a little difficult. The engine gets quite hot and that heat is directed around the rider’s calves, and tall boots are a better option than fashionable shorty boots in hot summer weather.

The engine was tuned to respond robustly at lower rpm, with lots to play with if you want to scratch it. Although the Z750s might fit in the same pigeonhole as a carb-equipped 600 or 750 four, the fuel coming through 34mm fuel-injected throttle bodies shows the vast leap forward in the way motorcycles work that such advances in technology provided. The six-speed gearbox is as good as you might expect from a Japanese manufacturer, though it is possibly a little difficult to find neutral on it when things are hot. Oil changes at least are made easier by an easy-to-access spin-off canister oil filter on the front of the engine, with hex head on the outside to make it easier to get on and off.

And all that power is handled readily by the basic but decent running gear. The Z750s is only a few kilos heavier than a V7, so it is easy to throw about, the big tyres soak up the ruts and grooves on my local roads like they’re not there and, despite being basic, the suspension does its job effectively. The twin two-pot Tokico calipers at the front grip the discs extremely well and the Kawasaki has the only rear brake pedal I’ve been able to use effectively in years, which is ironic because the front brake is usually all you need – in the dry, at least. There are adjustable levers and a welcome lack of unnecessary flashing displays, one benefit of the Z750s arriving before such things were deemed essential.

Out of production in 2007, the Z750s avoided the restrictions that Euro 3 regulations imposed too.

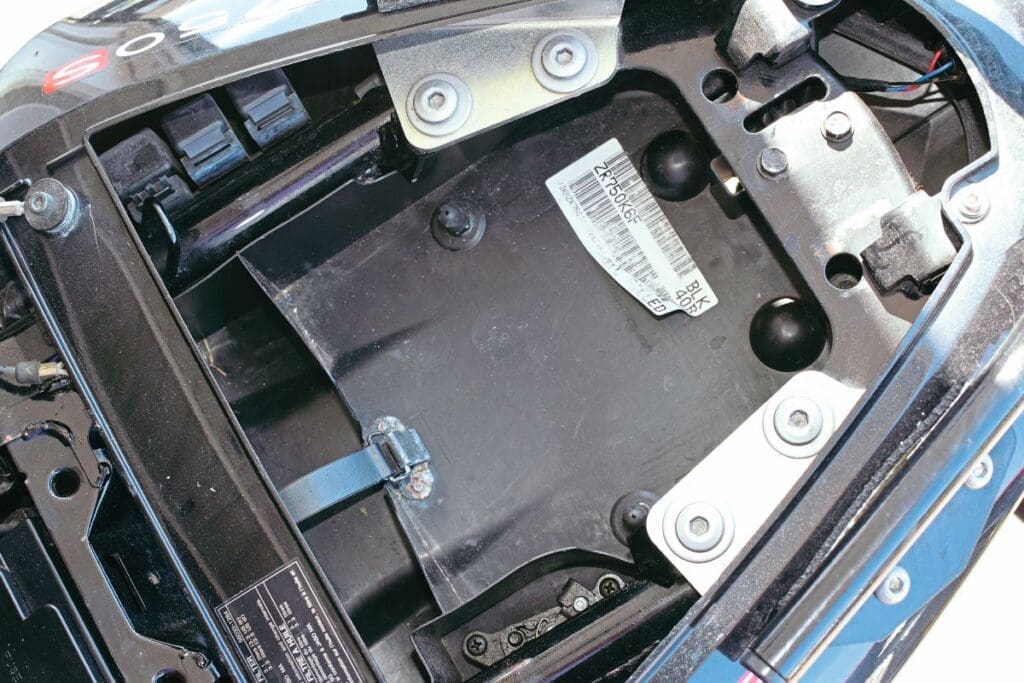

Bad points are minimal. The idiot lights are dim, and I frequently leave the indicators flashing. Getting the seat off is a right faff; you have to use an ignition key in a tiny hole under the rear mudguard and then wiggle the seat backwards. There is a handy hidey hole in there though, big enough for a sandwich and a can of pop. The immobiliser is an insurance premium cutting boost, but don’t lose the red key needed to reset it. That wonderful engine does eat the fat tyres, and they will not be cheap and will need replacing in pairs. And the basic-when-new suspension will now be useless, so budget for fork oil and service as a minimum and a rear shock most probably, so that’s £400 from Hagon or YSS. The side stand looks flimsy but probably isn’t, and there is no centre stand, sadly. What looks like cast aluminium frame panels on either side are in fact moulded plastic, and the square section swingarm looks like part of a piece of office furniture and could have done with a thicker coat of paint, given it is exposed to road muck. An aluminium arm would have been prettier.

The Z750S was only in production for a few years before being replaced by a more complicated upgrade and it never gained the profile of the Bandit, Fazer or Hornet – perhaps Kawasaki should, like its rivals, have given it a name rather than a number.

Delivering a more modern riding experience than your average retro, the Z750s may well be deserving of taking up space in your shed if you are looking for something enervating, useful and fast. You won’t mistake it for a super-sports 600, but the Z750S is nimble enough, with generous cornering clearance, plenty of grip and reassuring handling. The only real downside is the lack of any classic-style character, but it might grow on you. The cheapest insurance quote I had for it was £88 a year fully comprehensive, which is ludicrous.

The Z750s came in black, silver or blue. Black is the classier colour but is easier to mark. Standard bikes have a groovy pair of cast alloy grab handles. Tired Z750S examples can be had for about £1800 and less worn examples go up to £2500. This near mint one, if you are interested, you might just find if you look in the CBG classifieds. Why sell it if it is so good? Well, garage space is limited, and there is this Triumph TR65 Thunderbird I’ve been offered…

Specifications

ENGINE: 748cc DOHC liquid-cooled four-cylinder BORE/STROKE: 68.4mm/50.9mm CARBURATION: Four 34mm EFI throttle bodies COMPRESSION: 11.3:1 TRANSMISSION: Six-speed gearbox, IGNITION: Digital FRONT WHEEL: 120/70-17 REAR WHEEL: 180/55-17 FRONT SUSPENSION: 41mmHydraulic forks REAR SUSPENSION: Bottom link Uni-Trak, four-way rebound, seven-way preload FRONT BRAKE: Twin 300mm discs, twin two-pot Tokico calipers REAR BRAKE: Single 220mm single-piston caliper LENGTH: 82in (2080mm) SEAT HEIGHT: 32in ins (815mm) WHEELBASE: 56.1in (1425mm) DRY WEIGHT: 430lbs (195kg) FUEL TANK: 18 litre POWER: 110bhp TOP SPEED: 144mph

The last of the naked middleweight fours:

Suzuki Bandit

The Bandit could be the bike that started the craze for naked, monoshock sporty fours. Available first as a crazy-fast 400, with Japanese grey imports markedly faster and better made than Euro models, the Bandit soon inspired a 600, a 750 and a 1200, using detuned GSX-R DOHC four-cylinder engines. The Bandits were everywhere, being cheap, rapid, and easy to personalise with Renthal bars, twin headlights and noisy 4-1 exhausts. S models had a small nose fairing but did not capture the imagination of buyers. The Bandit was popular enough for owners to establish their own owners’ club and it was a sought-after machine among to in the street hooligan wing of motorcycling, especially in 1200cc format. Prices start at £800 for an early running model, with later revised frame models more highly priced, but the price of a Bandit is rising rapidly as nostalgia buying kicks in.

Honda Hornet

Honda’s Hornet was more respectable than the Bandit but also marginally faster and better made. It had a retuned 97bhp CBR600F motor, with carbs, and was bit revvy and vibratory to ride. Later models had a larger tank, while the high-level exhaust, while attractive, did make using throwover panniers difficult and reduced its touring potential. A Hornet S, made for a few years, had a nose fairing. The Hornet name survived and is now used on a 500 and 750 twin and a 1000cc four. Prices are low, with a tired Hornet 600 starting at £800.

Yamaha Fazer 600

Launched in 1998, the Fazer was the bestselling bike in the class in 1999. Fitted with a detuned and prettified Thundercat motor and R1 brakes, it was a long way from the pedestrian XJ600 it replaced. Enormous fun to ride, comfortable, fine handling, and rapid, it was very popular. Problems with the early model’s headlights saw many Fazers losing their nose fairings and being fitted with aftermarket headlights, and the fairing was redesigned to solve the problem on later models. An excellent motorcycle, killed by incoming Euro 3 regulations and replaced by the better but less exciting XJ6, a good early Fazer can be an excellent buy. Prices start at about £1200.

End times

By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the naked four was running out of steam – not because people did not want them, but because there was now a cheaper way of meeting the demand for fast middleweights and those emissions regulations were getting harder to negotiate. 650 and 700 twins became the way to fill this lucrative market niche. The big four Japanese bike makers took to using twin-cylinder middleweight drivetrains. These ‘had more character’ but were cheaper to make as they used half the parts (two pistons, two injectors, two exhausts) and put them in frames that were lighter and cheaper than those on the fours. Honda named its naked 650 the CB650F, even though it was a twin. Manufacturers also started making these generic twin-cylinder engines in China and India, and they have ended up with many different badges on their tanks. Today, you will find the four-cylinder engine in bigger bikes, but the middleweight multi-cylinder engine has largely vanished. If you want to experience the last of the old-school middleweight fours, these are the bikes to have.