Beware – large amounts of fun incoming!

Words by Oli ‘West Country’ Hulme, with photography by Gary ‘Hunk’ Chapman

It’s 1969. You are strolling out of the factory on a Friday night and your meagre apprentice wages are burning a hole in your back pocket. You are determined to go looking for wheels on Saturday morning, a copy of Motorcycle and Three-Wheeler Mechanics stuffed into your overalls. If you don’t want a scooter, and they were quickly slipping out of fashion, your limited financial resources might just run to a 125. Small British bikes are dead in the water. No matter how much the Government says you should be ‘Backing Britain,’ the Francis-Barnett Plover had been out of production for two years and that wasn’t going to cut it down at the bus stop. Your local bike shop might have an array of small Italian bikes, but those are mostly out of the range of your pocket. Honda tries to tempt you with a CB or SS125 twin, but they are a bit, well, weird, with lots of bits to worry about. Kawasaki isn’t here yet. Yamaha’s AS125 twin is quite groovy and impressively fast for a 125, while being classically good-looking with chromed tank panels. Suzuki had launched a similar bike to the Yamaha in 1966, the T125, which looked like a the T20 Super Six 250 twin that had shrunk in the wash and was not unattractive. This was mostly sold in Japan, but a select few also escaped into the international market. The engine for this first T125 came from an earlier 125cc two-stroke twin, the AS125, sold from 1963. And then, suddenly, there was a new mad-as-heck twin, with eye-popping styling: the Suzuki T125 Stinger.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

It looked like a tiny rocket ship and came with lines like nobody had ever seen before. Or since, some may say. Although it lacked a bit of top-end power compared to the Yamaha, the 15bhp engine was more tractable at lower speeds, and the kudos of being made by a championship-winning manufacturer helped sales too.

The T125 Stinger owes nothing to the earlier T125. However, the lines of the petrol tank were borrowed from those used on a pair of pressed-steel-framed 90 and 125cc single-cylinder models which had become available in 1967.

What the T125 Stinger did owe much of its origins to is a motorcycle Suzuki thought was going to be a massive seller, but wasn’t quite as successful as they would have liked. This was a fun little semi off-roader called the TC120 Trail Cat. This was one of Suzuki’s high-tech tiny bikes of the day, a motorcycle with a single-cylinder engine mated to dual-ratio gearbox to improve off-road performance. This used a kind-of trellis frame, but with a tubed cradle protecting the engine. The TC120 was a lot of fun, and that dual-ratio gearbox was used on several of Suzuki’s TC model off-roaders into the mid-1970s.

When Suzuki’s engineers got to work to create their new 125cc sports bike, they took the TC120 frame and called it the Tri-Form. They claimed it was race-proven, which it could sort-of lay claim to as Suzuki’s smaller race bikes did hang their motors off the top of the frame. They removed the off-roader’s protective cradle and came up with an all-new, twin-cylinder, two-stroke motor to hang off the frame rails.

The new engine bore a passing resemblance to a two-cylinder version of the new A50 motor which used a using disc valve with a carb on the end of the crank. The motor for the Stinger had twin two-stroke barrels mounted on a common crankcase. In operation, it was a conventional piston-ported twin with two downdraught carburettors and CCI auto lube. The crankcases were horizontally split, and the cylinders were angled upwards only a few degrees from being parallel with the road. The fins were longitudinal and adorned strikingly attractive cylinder heads with the barrel finning extended onto the crankcases. This was the sort of thing Japanese manufacturers used to come up with at the drop of a hat, rather than leaving their designs mired in development hell for half a decade before the machines appear, as happens today.

With styling that seemed to come from Saturn, and an engine using principles that were outside Suzuki’s usual modus operandi, it all came over as radical – even for the late 1960s. The bodywork and styling were something else, man.

With a frame the like of which had never been seen before, Suzuki put in one of those bonkers exhaust systems that the Japanese used to be so good at. A pair of pipes bent into a delicious series of curves swooping down either side, curving tightly over the top of the crankcases and then straight backwards, looking more like rocket engines than exhausts. Of course, being the late 1960s, they had to be as light as technologically possible to reduce overall weight and make the bike faster. To do this, they were made of materials with the structural rigidity of tinfoil and next-to-useless rust preventing quality for an extra-short shelf life. But that would be an issue for the second owner, of which no one cared.

It was like the designers got together in a conference…

“Let us create a powerful small engine, using all our engineering expertise, make it watch-like in its construction, and hang it off a ground-breaking frame of our own devising.”

“Yes, master, but what of the exhaust system, how shall we make those?”

“Oh, use some those bits of scrap metal out the back of the factory we used on noodle delivery tricycles that in turn used steel that was left over from the war, beat it out as thinly as possible, and give it an impossible bend then coat it with a layer of chrome less than a micron thick.”

As though to bamboozle and frustrate later restorers, these exhausts were chrome on the first models with black end cans, had fully chromed pipes on the year two models, and black with chromed end cans on the last year’s models. The black paint also had its work cut out preventing rust. Some models in Australasia, South America and the Caribbean came with low-slung exhausts with conventional silencers, too. All the profiles looked great, though.

Stylistically, it was one of the first Suzuki offerings to ditch the headlight nacelle and instead had had two clocks in a binocular housing with a very slim, tucked-away headlight. It came with three different tanks during the production run, too.

Not every market wanted a low-barred pseudo race bike, so Suzuki put wide, upright trials ‘bars on US models, and this created what was then known as a Canyon Racer. They were made to be used on the twisting roads of California’s hills above San Francisco and Los Angeles but given there was where most of the US bike press was based and where their brain-fried writers would test them, this design made sense. Cycle World writers were amazed by the Stinger, praising the ‘Italian’ styling, the finish, the chrome, and the brakes, and raved about the performance.

“The new Suzuki T-125 owner will be convinced he has put in an order for a fabled racing iron. If he stops to consider for a moment, he will discover he also has ordered smooth, vibrationless, quiet, everyday transportation, a delightful machine which is sufficiently flexible and docile for wife or galfriend to ride, and a bike that is sporting enough to please the teen-aged motor sophisticate. That’s a very large order for a very small motorcycle. The Suzuki T-125 Stinger fills that order in every respect.” – Cycle World, February 1969.

In the real world, buyers found that the Stinger followed Japanese design principles of the day in the handling department. That is, the forks and shrouded shocks were cheap and bouncy, the dampers not knowing if they were coming or going, and the brakes were basic and just about effective on wet European roads. But as the bike weighed only a tiny amount, this was not a major issue.

In Japanese and European markets, the bikes came with slightly raised or even flat ‘bars to give the Stinger an aggressive café racer stance.

The little twin also came with a 90cc engine. While it was commonly called the Stinger, it was also called the Wolf in the Far East and Australasia. Suzuki said this model, with a slightly different tank, was designed to “evoke the image of a wolf dashing toward its prey.” It was also named the Flying Leopard in some European countries.

The engine was, Suzuki claimed, designed for high-power, high-speed performance, and generated maximum horsepower of 15.1bhp at 9000rpm and a top speed of 80mph, even more. On the showroom floor, the Stinger was designed primarily to take on Yamaha’s feisty 125cc AS1 twin.

While it was slightly outperformed in the top speed stakes by the Yamaha AS1 and by a few pared-down-to-the-bone Italian bikes with race tuning, it outperformed Honda offerings and was notably rapid with superior power delivery. Today, it will wipe the floor with any modern learner-legal 125, weighing a fraction of current models.

The Stinger wasn’t quite as quick as the Yamaha, but Suzuki had nailed two-stroke power delivery rather than out-and-out power better than its tuning-fork badged rival. As with the 250cc twins it made, Suzuki’s power was rather more useable than Yamaha’s, and indeed what was produced was sometimes more like a four-stroke than a two-stroke, a trick it pulled off again with the GT triples. The Stinger was a smooth accelerating machine, the fuel heading into the downdraft carbs effectively.

From a casual glance, the Stinger was like nothing on earth – and in a good way. Everything about it was different, and while the first-year models were finished in a rather restrained blue or red with a splash of chrome, the second-year – and third-year – models made up for the lack of shiny bits by being finished in startlingly day-glo green or gold.

And then, almost as soon as it got started, it was gone. In 1971, with just three years in showrooms, the Stinger vanished. Suzuki was left with some very prosaic 125s to sell, including the enormously dated home-marketed K125, with a twin-port, single-cylinder engine that remarkably stayed in production until 1990, and the commuter special B120P, successor to the Bloop. There was a whole gamut of TS and TC off-roaders and an early version of the balloon-tyred Van Van. Given that this period also saw Suzuki produce blisteringly fast road racers and even the disastrous RE5 rotary, one must wonder what else was in the saki other than rice.

In 1975, the Stinger’s successor arrived in the shape of the GT125. It had nothing in common with the earlier bike, apart from the con rods and pistons, and while it looked more respectable, it was much rawer, with a decidedly hooligan element to its performance.

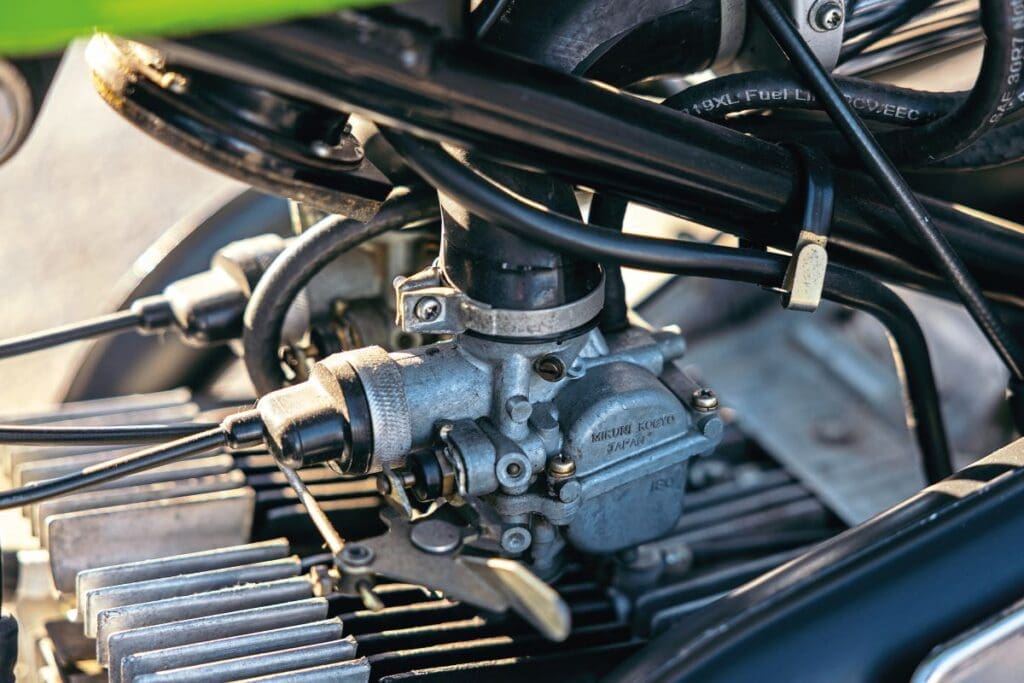

Today, the little Suzuki Stinger is still a showstopper. Enthusiasts spend years and small fortunes returning them to showroom condition. And there hangs the problem for the would-be Stinger owner today: the major barrier, or challenge, is the difficulty of finding parts. Although it shares a few bits with other Suzuki models of the period, much is simply unique to the model. Take, for instance, the carburettors. The Italians, when mounting carbs to an engine with a flat layout, would either fit long, curved inlets or carbs with remote float chambers. Suzuki went in a different direction and got Mikuni to make downdraft carbs with horizontal slides and cast-in float bowls. Good luck finding parts for those. There was a twin-pipe, single unit, vacuum-operated petrol tap too.

The seat was unusual as the rear cutaway allowed it to hinge backwards, giving plenty of access to the underseat area; the rear mudguard is unique and unobtainable. There were different front mudguards on the Wolf and the Stinger. It came with three different tanks, too: the afore-mentioned different exhaust pipes, a selection of different electrical parts, and different seats.

And there’s the rub. You could buy a Stinger project, if you could find one, for perhaps £1, and then spend years collecting parts, paying painters and chromers and engineers hundreds, if not thousands, of pounds and spend your evenings diligently bending over what may one day be your pride and joy – which is, of course, one of the pleasures of classic motorcycling. Or you could just pop down to Newark tomorrow and hand over £4500 (the price of a modern Japanese performance 125), stick a boot on the left-hand kick-start, and head up the road in a cloud of blue smoke and nostalgia. Which is also one of the pleasures of classic motorcycling. You pay your money, and you make your choice…

Oli’s view

Why would anybody want a tiny little Suzuki stroker you can’t get bits for? With skinny tyres and questionable suspension? Because it will be as mad as a sack full of badgers, cute as your first girl/boyfriend, and will turn heads everywhere you go. You’ll find your misspent youth flooding back into your memory. Admittedly, you could buy a big, chunky classic for £4500, but where’s the fun in that? Riding small bikes fast is way better than riding big bikes slowly. Every bike less than 200cc I’ve ridden has left me with a huge grin on my face. And everybody loves them. Turn up to a meet on one, park it next to a Gold Star, and see the reaction. Tiny bikes equals huge fun. Admittedly, my build makes me look completely absurd on one, but if you are 5ft 6in tall and nine stone, the world is your mollusc.

Matt’s view

This is purely my way of thinking, but bikes are for riding, for feeling the journey, and even tinkering with, not being seen on. I care as much about what others think as I do about East Enders Street.

But then I saw this bike: the immaculate, eye-poppingly bright Suzuki Stinger. Bizarrely, the first thing I did was pick it up – which I could – as it looks so minimal, so small. Then there is the detail, which is as good as any British 650 twin or Italian multi-cylinder. The style is unique, brave, and if anything can excite a young’un, it’s a Stinger. Or Razzle.

Even sitting on it felt great and raised a smile. I didn’t ride this one, you see, but a friend’s, and I felt my helmet would stretch, I was smiling so much. All the revs, all the time, crouching down, finding narrow streets with tall buildings just so I could hear it reverb… it did something to me. Oli’s right – the best fun riding can be had on a small bike and, at last, I’m starting to understand the craze for Japanese 50s, 125s and 200s. I’ve been missing out.

MANUFACTURED: 1968-1971 ENGINE: Air-cooled, two-stroke twin BORE / STROKE: 43x43mm CAPACITY: 124cc POWER: 15.1bhp @ 8500rpm LUBRICATION: Two-stroke oil injection IGNITION: Points CARBURETTOR: Twin Mikuni TRANSMISSION: Chain GEARBOX: Five-speed foot change FRAME: Tubular construction FRONT SUSPENSION: Telescopic forks, hydraulic damping REAR SUSPENSION: Twin oil-damped shocks BRAKE: 5.5in sls drum TYRES: 2.50 x 18 front; 2.75 x 18 rear WHEELBASE: 1098mm DRY WEIGHT: 96kg TOP SPEED: 80mph

SPECIALISTS

AberMoto: www.abermoto.co.uk/

Robinsons: www.robinsonsfoundry.co.uk

Marcel Vlaandere: www.classicsuzukiparts.nl

OWNERS’ CLUB

Suzuki Owners’ Club: suzukiownersclub.co.uk

Enormous thanks to Motorcycle Investment Services of Newark for the loan of its T125 Stinger. At the time of writing, this truly immaculate example is still available, at £4500. Visit misukltd.com